9F1 Global Studies

Section outline

-

Tēnā tātou, Ko Logan tēnēi,

Nau mai, haere mai ki te akoako mō te tau.

Hello and welcome to your Global Studies online page for 2022. Our first learning context for the year is

Developing our research capabilities in relation to how communities cope with, and recover from, the social and environmental impacts of human disasters. This will supply you with a deeper understanding of some of the current events that are in process around our local and global communities presently.

We will begin our exploration by looking at some historical examples of local disasters (such as the sinking of the Orpheus in the Manukau harbour) and how our communities succeeded and struggled in their response to the social and environmental impacts of a human disaster.

Ahakoa he iti, he pounamu

-

What is a disaster?

Disasters are serious disruptions to the functioning of a community that exceed its capacity to cope using its own resources. Disasters can be caused by natural, man-made and technological hazards, as well as various factors that influence the exposure and vulnerability of a community

https://sites.google.com/mhjc.school.nz/year-9-nghere-whnau/home -

Remembering the Orpheus 160 years on

“What you see and what you hear depends a great deal on where you are standing. It also depends on what sort of person you are.” CS Lewis

Standing on Whatipu Beach yesterday with colleagues from our museum and more than a hundred others, it seemed to me that CS Lewis had it about right. Commemorating the heart-rending loss of life on Manukau Bar 160 years ago, we were reminded of the many perspectives that surround daily life.

There is no dispute over the core facts: HMS ORPHEUS foundered in fair weather on 7 February 1863; 189 lives were lost or unaccounted for; the tragedy remains New Zealand’s worst maritime disaster. But the circumstances are another matter.

In his speech yesterday, Taumata member Te Warena Taua reminded us that the ship was perceived by his people as a threatening force; nevertheless, courageous Maori made a major contribution to saving life, with recognition both in cash and in medals awarded by the Royal Humane Society.

https://sites.google.com/mhjc.school.nz/year-9-nghere-whnau/home/case-study-1-the-orpheus-disaster -

WALT...

Research a historical event.

Present information in an effective manner.

What is a disaster?

Disasters are serious disruptions to the functioning of a community that exceed its capacity to cope using its own resources. Disasters can be caused by natural, man-made and technological hazards, as well as various factors that influence the exposure and vulnerability of a community

What are hazards?

Natural hazards are naturally occurring physical phenomena. They can be:

Geophysical: a hazard originating from solid earth (such as earthquakes, landslides and volcanic activity)

Hydrological: caused by the occurrence, movement and distribution of water on earth (such as floods and avalanches)

Climatological: relating to the climate (such as droughts and wildfires)

Meteorological: relating to weather conditions (such as cyclones and storms)

Biological: caused by exposure to living organisms and their toxic substances or diseases they may carry (such as disease epidemics and insect/animal plagues)

Man-made and technological hazards are events that are caused by humans and occur in or close to human settlements. They include complex emergencies, conflicts, industrial accidents, transport accidents, environmental degradation and pollution.

While hazards may be natural and inevitable, disasters are not.

Disasters happen when a community is:

“not appropriately resourced or organized to withstand the impact, and whose population is vulnerable because of poverty, exclusion or socially disadvantaged in some way” (Mizutori, 2020).

-

WALT...

Research a historical event.

Present information in an effective manner.

What is a disaster?

Disasters are serious disruptions to the functioning of a community that exceed its capacity to cope using its own resources. Disasters can be caused by natural, man-made and technological hazards, as well as various factors that influence the exposure and vulnerability of a community

What are hazards?

Natural hazards are naturally occurring physical phenomena. They can be:

Geophysical: a hazard originating from solid earth (such as earthquakes, landslides and volcanic activity)

Hydrological: caused by the occurrence, movement and distribution of water on earth (such as floods and avalanches)

Climatological: relating to the climate (such as droughts and wildfires)

Meteorological: relating to weather conditions (such as cyclones and storms)

Biological: caused by exposure to living organisms and their toxic substances or diseases they may carry (such as disease epidemics and insect/animal plagues)

Man-made and technological hazards are events that are caused by humans and occur in or close to human settlements. They include complex emergencies, conflicts, industrial accidents, transport accidents, environmental degradation and pollution.

While hazards may be natural and inevitable, disasters are not.

Disasters happen when a community is:

“not appropriately resourced or organized to withstand the impact, and whose population is vulnerable because of poverty, exclusion or socially disadvantaged in some way” (Mizutori, 2020).

- This week

-

Case Study 2 - the Spanish Flu in the Pacific

An influenza pandemic (world-wide epidemic) struck New Zealand between October and December 1918, just at the war’s end. No other event has killed so many New Zealanders in so short a time.

In only two months, about 9,000 New Zealanders died — about half as many as in the whole of the First World War. Around the world, the pandemic infected hundreds of millions, and killed almost three times as many as WWI.

Origins of the infection

Historians now believe the pandemic was related to swine flu. They also believe it’s likely that American soldiers were first infected in Kansas and carried the virus to Europe early in 1918. Returning troops brought it back to New Zealand, first to military camps such as Featherston and Trentham, then spreading it around the country as they returned home.

Many people believed the virus arrived in New Zealand aboard the RMS Niagara with the Prime Minister, William Massey, and Finance Minister, Sir Joseph Ward, who were returning from meeting the Imperial War Cabinet in London. However, the virus was already established in New Zealand by this point in October 1918, so this seems unlikely.

Parliament’s response to the pandemic

The House kept sitting through the height of the influenza epidemic, but Prime Minister Massey was forced to adjourn twice, and close the public galleries, because of the severity of the epidemic.

At least 18 MPs were laid low, and two died from the virus: the Labour Party leader, Alfred Hindmarsh, and the Reform Party’s David Buick. As a result, Harry Holland became the new leader of the Labour Party.

Māori suffered particularly heavily from the virus, with about 2,500 deaths around the country. As historians report, their MPs did what they could to help.

- Tau Henare, MP for Northern Māori and great-grandfather of the later MP Tau Henare, “turned his own house into a hospital and, with his parents’ help, nursed the sick of the district”. (His wife had died early in the epidemic in Auckland, where their children were at school.)” [1]

- Dr Māui Pōmare, MP for Western Māori and Minister for Native Affairs, was struck down at the beginning of the epidemic, and had a relapse after attempting to get up too soon. But by late November he was well enough to attend his electorate. “Starting with Manawatu on 24 November, Pōmare visited all the principal pā in the western half of the North Island, and reached Thames on 16 December. The Levin Chronicle described his car as a ‘miniature pharmacy’ on wheels, and wherever he stopped he left supplies of medicine.”[2]

Legislative legacy of the pandemic

Once the pandemic was over, the Government set up a Royal Commission to investigate how the crisis had been handled. The Department of Public Health had come in for heavy criticism.

One of the Commission’s recommendations was for an overhaul of the Health Act, to consolidate and simplify the existing legislation. The result — the Health Act 1920 — has been praised as a model piece of health legislation. It was “so well drafted that it survived with only minor amendments until the 1956 Health Act, which itself still followed the general pattern of the 1920 Act”.

Historian Geoffrey Rice has described the Health Act 1920 as “the most useful legacy of the 1918 influenza pandemic”.

Sources and more information

You can get more information about the 1918 influenza pandemic from the New Zealand History website, Nga korero a ipurangi o Aotearoa, and from the books listed below:

The House: New Zealand’s House of Representatives 1854–2004 (Martin, 2004).

Black November: the 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand (Rice, 2005).

[1] Source: Black November, p. 175

[2] Source: Black November, p. 181.

-

Case Study 2 - the Spanish Flu in the Pacific

An influenza pandemic (world-wide epidemic) struck New Zealand between October and December 1918, just at the war’s end. No other event has killed so many New Zealanders in so short a time.

In only two months, about 9,000 New Zealanders died — about half as many as in the whole of the First World War. Around the world, the pandemic infected hundreds of millions, and killed almost three times as many as WWI.

Origins of the infection

Historians now believe the pandemic was related to swine flu. They also believe it’s likely that American soldiers were first infected in Kansas and carried the virus to Europe early in 1918. Returning troops brought it back to New Zealand, first to military camps such as Featherston and Trentham, then spreading it around the country as they returned home.

Many people believed the virus arrived in New Zealand aboard the RMS Niagara with the Prime Minister, William Massey, and Finance Minister, Sir Joseph Ward, who were returning from meeting the Imperial War Cabinet in London. However, the virus was already established in New Zealand by this point in October 1918, so this seems unlikely.

Parliament’s response to the pandemic

The House kept sitting through the height of the influenza epidemic, but Prime Minister Massey was forced to adjourn twice, and close the public galleries, because of the severity of the epidemic.

At least 18 MPs were laid low, and two died from the virus: the Labour Party leader, Alfred Hindmarsh, and the Reform Party’s David Buick. As a result, Harry Holland became the new leader of the Labour Party.

Māori suffered particularly heavily from the virus, with about 2,500 deaths around the country. As historians report, their MPs did what they could to help.

- Tau Henare, MP for Northern Māori and great-grandfather of the later MP Tau Henare, “turned his own house into a hospital and, with his parents’ help, nursed the sick of the district”. (His wife had died early in the epidemic in Auckland, where their children were at school.)” [1]

- Dr Māui Pōmare, MP for Western Māori and Minister for Native Affairs, was struck down at the beginning of the epidemic, and had a relapse after attempting to get up too soon. But by late November he was well enough to attend his electorate. “Starting with Manawatu on 24 November, Pōmare visited all the principal pā in the western half of the North Island, and reached Thames on 16 December. The Levin Chronicle described his car as a ‘miniature pharmacy’ on wheels, and wherever he stopped he left supplies of medicine.”[2]

Legislative legacy of the pandemic

Once the pandemic was over, the Government set up a Royal Commission to investigate how the crisis had been handled. The Department of Public Health had come in for heavy criticism.

One of the Commission’s recommendations was for an overhaul of the Health Act, to consolidate and simplify the existing legislation. The result — the Health Act 1920 — has been praised as a model piece of health legislation. It was “so well drafted that it survived with only minor amendments until the 1956 Health Act, which itself still followed the general pattern of the 1920 Act”.

Historian Geoffrey Rice has described the Health Act 1920 as “the most useful legacy of the 1918 influenza pandemic”.

Sources and more information

You can get more information about the 1918 influenza pandemic from the New Zealand History website, Nga korero a ipurangi o Aotearoa, and from the books listed below:

The House: New Zealand’s House of Representatives 1854–2004 (Martin, 2004).

Black November: the 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand (Rice, 2005).

[1] Source: Black November, p. 175

[2] Source: Black November, p. 181.

-

Case Study 2 - the Spanish Flu in the Pacific

An influenza pandemic (world-wide epidemic) struck New Zealand between October and December 1918, just at the war’s end. No other event has killed so many New Zealanders in so short a time.

In only two months, about 9,000 New Zealanders died — about half as many as in the whole of the First World War. Around the world, the pandemic infected hundreds of millions, and killed almost three times as many as WWI.

Origins of the infection

Historians now believe the pandemic was related to swine flu. They also believe it’s likely that American soldiers were first infected in Kansas and carried the virus to Europe early in 1918. Returning troops brought it back to New Zealand, first to military camps such as Featherston and Trentham, then spreading it around the country as they returned home.

Many people believed the virus arrived in New Zealand aboard the RMS Niagara with the Prime Minister, William Massey, and Finance Minister, Sir Joseph Ward, who were returning from meeting the Imperial War Cabinet in London. However, the virus was already established in New Zealand by this point in October 1918, so this seems unlikely.

Parliament’s response to the pandemic

The House kept sitting through the height of the influenza epidemic, but Prime Minister Massey was forced to adjourn twice, and close the public galleries, because of the severity of the epidemic.

At least 18 MPs were laid low, and two died from the virus: the Labour Party leader, Alfred Hindmarsh, and the Reform Party’s David Buick. As a result, Harry Holland became the new leader of the Labour Party.

Māori suffered particularly heavily from the virus, with about 2,500 deaths around the country. As historians report, their MPs did what they could to help.

- Tau Henare, MP for Northern Māori and great-grandfather of the later MP Tau Henare, “turned his own house into a hospital and, with his parents’ help, nursed the sick of the district”. (His wife had died early in the epidemic in Auckland, where their children were at school.)” [1]

- Dr Māui Pōmare, MP for Western Māori and Minister for Native Affairs, was struck down at the beginning of the epidemic, and had a relapse after attempting to get up too soon. But by late November he was well enough to attend his electorate. “Starting with Manawatu on 24 November, Pōmare visited all the principal pā in the western half of the North Island, and reached Thames on 16 December. The Levin Chronicle described his car as a ‘miniature pharmacy’ on wheels, and wherever he stopped he left supplies of medicine.”[2]

Legislative legacy of the pandemic

Once the pandemic was over, the Government set up a Royal Commission to investigate how the crisis had been handled. The Department of Public Health had come in for heavy criticism.

One of the Commission’s recommendations was for an overhaul of the Health Act, to consolidate and simplify the existing legislation. The result — the Health Act 1920 — has been praised as a model piece of health legislation. It was “so well drafted that it survived with only minor amendments until the 1956 Health Act, which itself still followed the general pattern of the 1920 Act”.

Historian Geoffrey Rice has described the Health Act 1920 as “the most useful legacy of the 1918 influenza pandemic”.

Sources and more information

You can get more information about the 1918 influenza pandemic from the New Zealand History website, Nga korero a ipurangi o Aotearoa, and from the books listed below:

The House: New Zealand’s House of Representatives 1854–2004 (Martin, 2004).

Black November: the 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand (Rice, 2005).

[1] Source: Black November, p. 175

[2] Source: Black November, p. 181.

-

Ngā hiahia titiro ki te tiimatatanga, ā, ka kite māramatanga ai tātou te mutunga e.

E tekau tau: ka kimi te whakapapa o te hītori o te motu nei/Year 10: The histories of Te Ika-a-Maui and Te-Waka-a-Maui/Aotearoa-New Zealand

Āta whakaaro mō te wā katoa/The Big Idea to reflect on over the span of this course:

What are the key concepts, contexts, and ways of understanding/interpreting the world must I focus on, if I am to succeed within the new evolution of the NCEA curriculum?

(which begins in schools from next year - across all subjects). Basically, the transition throughout this year in History class is one where we must strive to grasp for things that are outside of our grasp; because the curriculum does not care if you've been taught/learnt this stuff by next year - it will still requiree the standard it sets regardless.

Our context is whanaungatanga - we will explore the different networks of meaning and understanding that constitutes this notion; and, begin learnig how to apply it within an analysis,

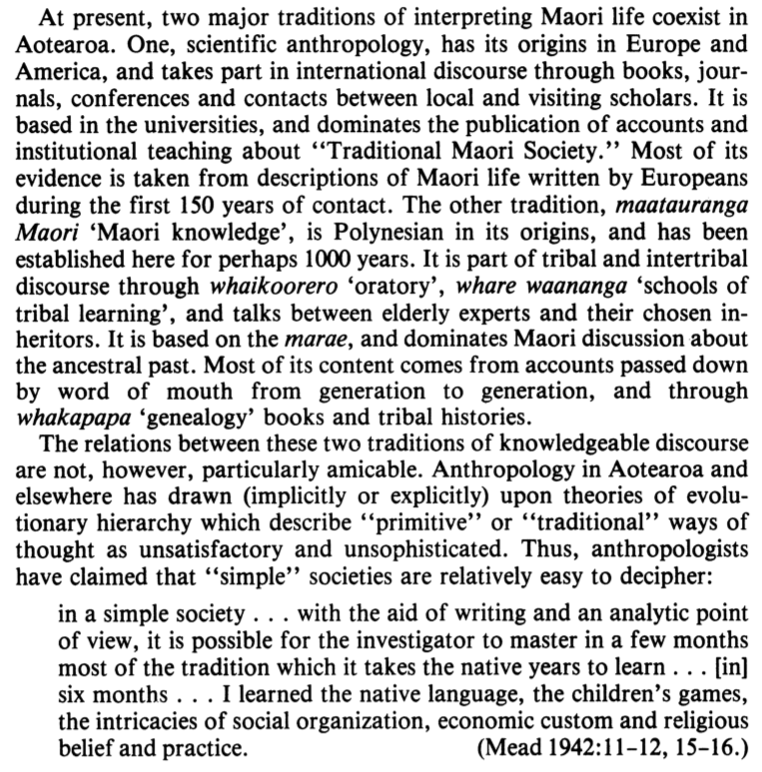

Professor Dame Anne Salmond is one of our nation's, and the world's, most respected anthropologists; her words below have relevance for us this term.

-

Students will

- work in groups to conduct research, which may include:

- finding primary and secondary sources on the history of Te Kooti and Wharekauri in the 19th century

- exploring these sources through the lenses of whakapapa and whanaungatanga

-

Explore how people’s understanding of and engagement with whakapapa, whanaungatanga, and tūrangawaewae have shaped the past.

Explore how people’s understanding of and engagement with whakapapa, whanaungatanga, and tūrangawaewae have shaped the past.Explore how people’s understandings of and engagement with mana have shaped the past.

-

REFLECT / WHAIWHAKAARO learning intentions:

- We are REFLECTING on the role of whānau in MHJC

Explore the ethical dimensions of historical interpretation

Explore the ethical dimensions of historical interpretationRecognise that histories are constructed from sources and may differ in their construction

Develop an understanding of a historical research process including the strengths and limitations of different historical sources

Explore the importance of vā in shaping historical identities.

-

REFLECT / WHAIWHAKAARO learning intentions:

- We are REFLECTING on the role of whānau in MHJC

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING different connections to the theories and practices of whanaungatanga

- We are EXPLORING the conceptualisation of the Māori world within the context of te Ao Mārama

- We are EXPLORING ngā rangahau mō te kawa o te marae o Tainui

-

REFLECT / WHAIWHAKAARO learning intentions:

- We are REFLECTING on the role of whānau in MHJC

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING different connections to the theories and practices of whanaungatanga

- We are EXPLORING the conceptualisation of the Māori world within the context of te Ao Mārama

- We are EXPLORING ngā rangahau mō te kawa o te marae o Tainui

-

PLAN & DO / WHAKAMAHI learning intentions:

- We are PLANNING to prepare a presentation of our research so that we can demonstarte whakamārama to the local tangata whenua at Te Whare Wānanga o Ōwairoa.

REFLECT / WHAIWHAKAARO learning intentions:

- We are REFLECTING on the role of whānau in MHJC

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING different connections to the theories and practices of whanaungatanga

- We are EXPLORING the conceptualisation of the Māori world within the context of te Ao Mārama

- We are EXPLORING ngā rangahau mō te kawa o te marae o Tainui

Explore the role of pūrākau and pakiwaitara in constructing and sustaining histories.

Explore the ways that power has been exercised in the past, including the diverse experiences and effects of power.

Develop a historical narrative using historical concepts and selected evidence.

-

FOCUS / ARONGA learning intentions:

- We are FOCUSING on how our economic system has evolved into our present-day.

- We are FOCUSING on describing how the foundational values can of an economy can help to clarify and explain how the economy operates

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING the origins of capitalism by researching the history of our modern economy

- We are EXPLORING the consequences of capitalism for people and the planet and how this connects to the foundational value of the 'profit motive'.

- We are EXPLORING the possible future of our economy to conceptualise how this it might connect to the idea/value of hauora

PLAN & DO / WHAKAMAHI learning intentions:

- We are PLANNING to prepare a presentation of our research so that we can demonstarte whakamārama to the local tangata whenua at Te Whare Wānanga o Ōwairoa.

REFLECT / WHAIWHAKAARO learning intentions:

- We are REFLECTING on the role of whānau in MHJC

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING different connections to the theories and practices of whanaungatanga

- We are EXPLORING the conceptualisation of the Māori world within the context of te Ao Mārama

- We are EXPLORING ngā rangahau mō te kawa o te marae o Tainui

-

FOCUS / ARONGA learning intentions:

- We are FOCUSING on how our economic system has evolved into our present-day.

- We are FOCUSING on describing how the foundational values can of an economy can help to clarify and explain how the economy operates

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING the origins of capitalism by researching the history of our modern economy

- We are EXPLORING the consequences of capitalism for people and the planet and how this connects to the foundational value of the 'profit motive'.

- We are EXPLORING the possible future of our economy to conceptualise how this it might connect to the idea/value of hauora

-

Kia ora...

Success Criteria:

Understand the research pathways available this term

Activities:

- Introduction to economics part 1 and 2 - the basic s and key words

Further Learning:

wordlist/concept list: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1tg0lWRfyu1G0RVNp1JauxRgL8IIrzAR2F84CtU1vNlA/edit?usp=sharingEXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING the origins of capitalism by researching the history of our modern economy

- We are EXPLORING the consequences of capitalism for people and the planet and how this connects to the foundational value of the 'profit motive'.

- We are EXPLORING the possible future of our economy to conceptualise how this it might connect to the idea/value of hauora

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING the origins of capitalism by researching the history of our modern economy

- We are EXPLORING the consequences of capitalism for people and the planet and how this connects to the foundational value of the 'profit motive'.

- We are EXPLORING the possible future of our economy to conceptualise how this it might connect to the idea/value of hauora

-

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING the origins of capitalism by researching the history of our modern economy

- We are EXPLORING the consequences of capitalism for people and the planet and how this connects to the foundational value of the 'profit motive'.

- We are EXPLORING the possible future of our economy to conceptualise how this it might connect to the idea/value of hauora

Kia ora...

Success Criteria:

recognise and identify the three basic questions of economics

recognise and identify different economic systems

Activities:

- Q&A slldeshow

- Reading, watching and quiz on the foundations of economic systems

-

Kia ora...

Success Criteria:

To analyse the logic of the arguments put forward to support beliefs about the economic system.

Activities:

- The Great Debate - Chloe and David

- Inquiry into economic inequality and military conflict

Further Learning:

See google classroom

-

Kia ora...

Success Criteria:

To have accurate notes to reflect on economic systems

Activities:

- Summary of learning

REFLECT / WHAIWHAKAARO learning intentions:

- We are REFLECTING on the impacts that the capitalist economy has had on society [people and the planet]

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING the origins of capitalism by researching the history of our modern economy

- We are EXPLORING the consequences of capitalism for people and the planet and how this connects to the foundational value of the 'profit motive'.

- We are EXPLORING the possible future of our economy to conceptualise how this it might connect to the idea/value of hauora

-

Kia ora...

Success Criteria:

To have accurate notes to reflect on economic systems

Activities:

- Summary of learning

REFLECT / WHAIWHAKAARO learning intentions:

- We are REFLECTING on the impacts that the capitalist economy has had on society [people and the planet]

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING the origins of capitalism by researching the history of our modern economy

- We are EXPLORING the consequences of capitalism for people and the planet and how this connects to the foundational value of the 'profit motive'.

- We are EXPLORING the possible future of our economy to conceptualise how this it might connect to the idea/value of hauora

-

PLAN & DO / WHAKAMAHI learning intentions:

- We are PLANNING to apply our learning to our present-day state of affairs, so that we can innovate and share ideas for how we might construct a just economic system in the future.

REFLECT / WHAIWHAKAARO learning intentions:

- We are REFLECTING on the impacts that the capitalist economy has had on society [people and the planet]

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING the origins of capitalism by researching the history of our modern economy

- We are EXPLORING the consequences of capitalism for people and the planet and how this connects to the foundational value of the 'profit motive'.

- We are EXPLORING the possible future of our economy to conceptualise how this it might connect to the idea/value of hauora

-

PLAN & DO / WHAKAMAHI learning intentions:

- We are PLANNING to apply our learning to our present-day state of affairs, so that we can innovate and share ideas for how we might construct a just economic system in the future.

Kia ora...

Success Criteria:

Understanding the causes of the Taranaki invasion in 1860/61

Activities:

- Research round: Parihaka - social contexf parts 1 & 2

Further Learning:

see google classroom documentaries -

PLAN & DO / WHAKAMAHI learning intentions:

- We are PLANNING to apply our learning to our present-day state of affairs, so that we can innovate and share ideas for how we might construct a just economic system in the future.

-

Kia ora taatou, our context for this term is Kia Mana Āke - which at MHJC we interpret as Growing Greatness.

Our exploration of this whakataukī is going to be directed on two levels. First, we will be aiming to situate ourselves within the study - the reasons for this are communicated in the whakataukī:

"Inā kei te mohio koe ko wai koe, i anga mai koe i hea, kei te mohio koe, kei te anga atu ki hea"

If you know who you are and where you are from, then you will know where you are going

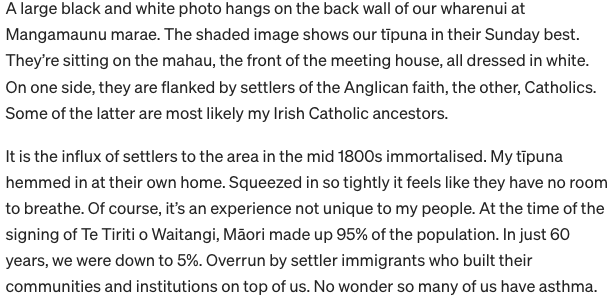

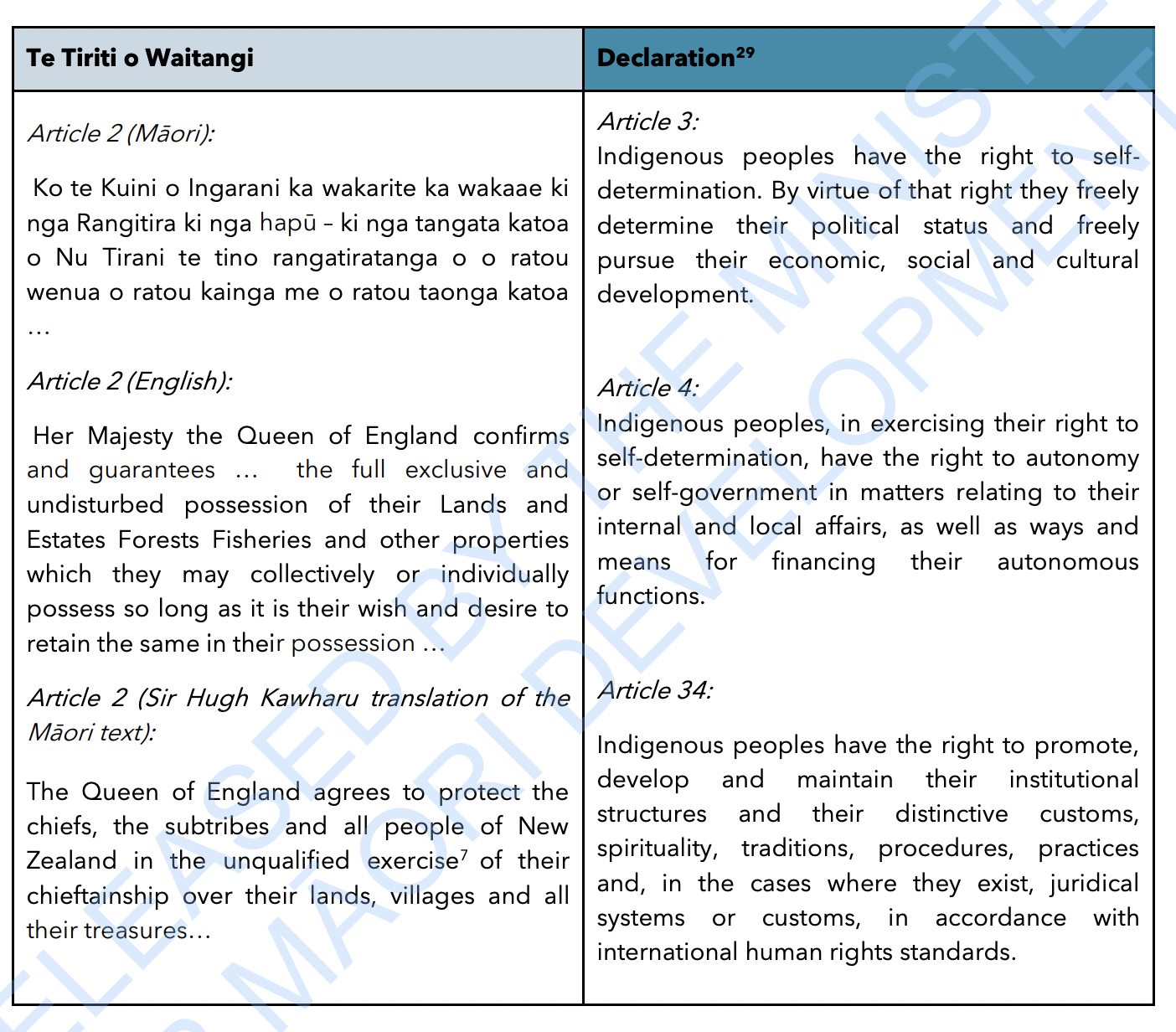

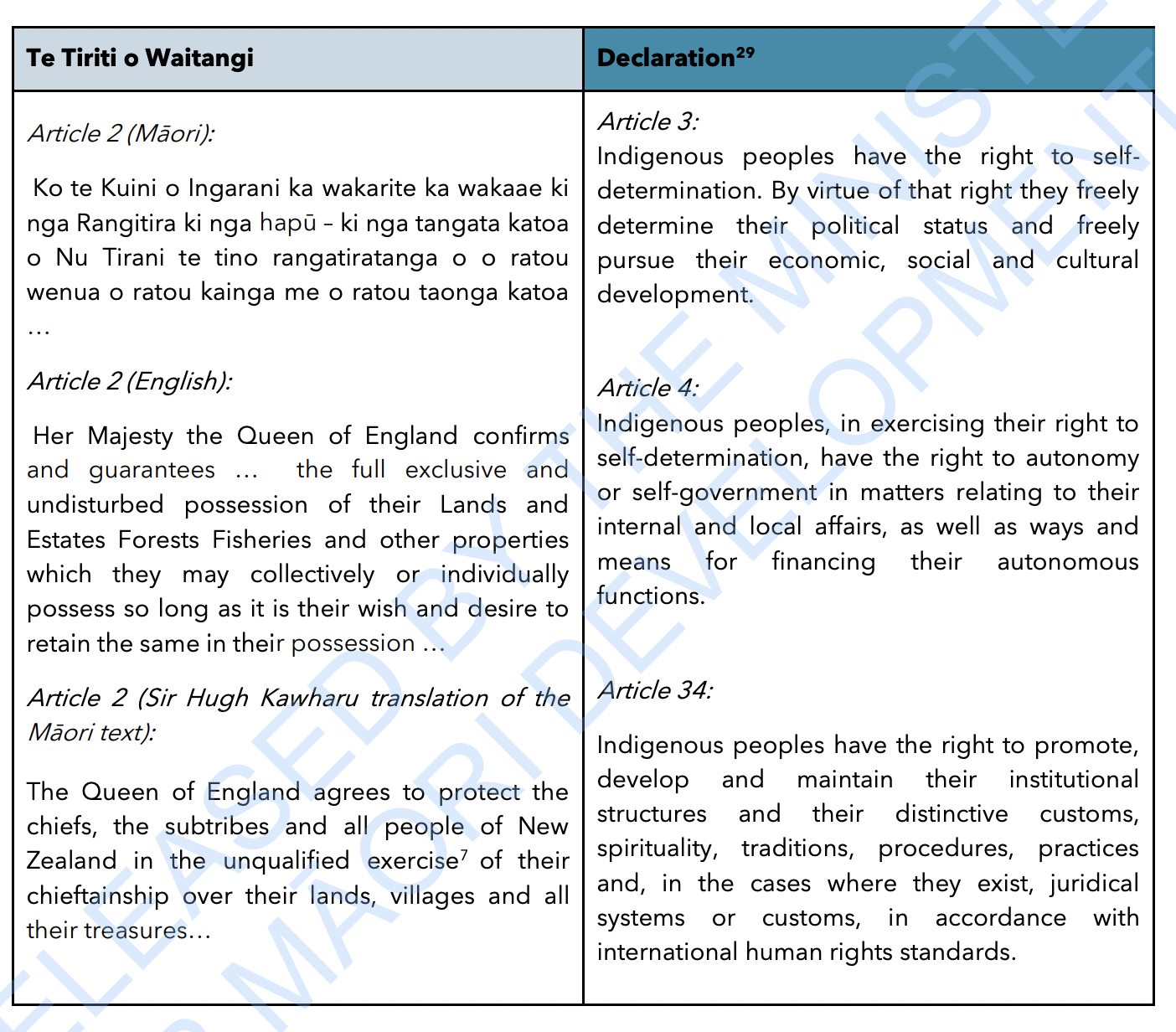

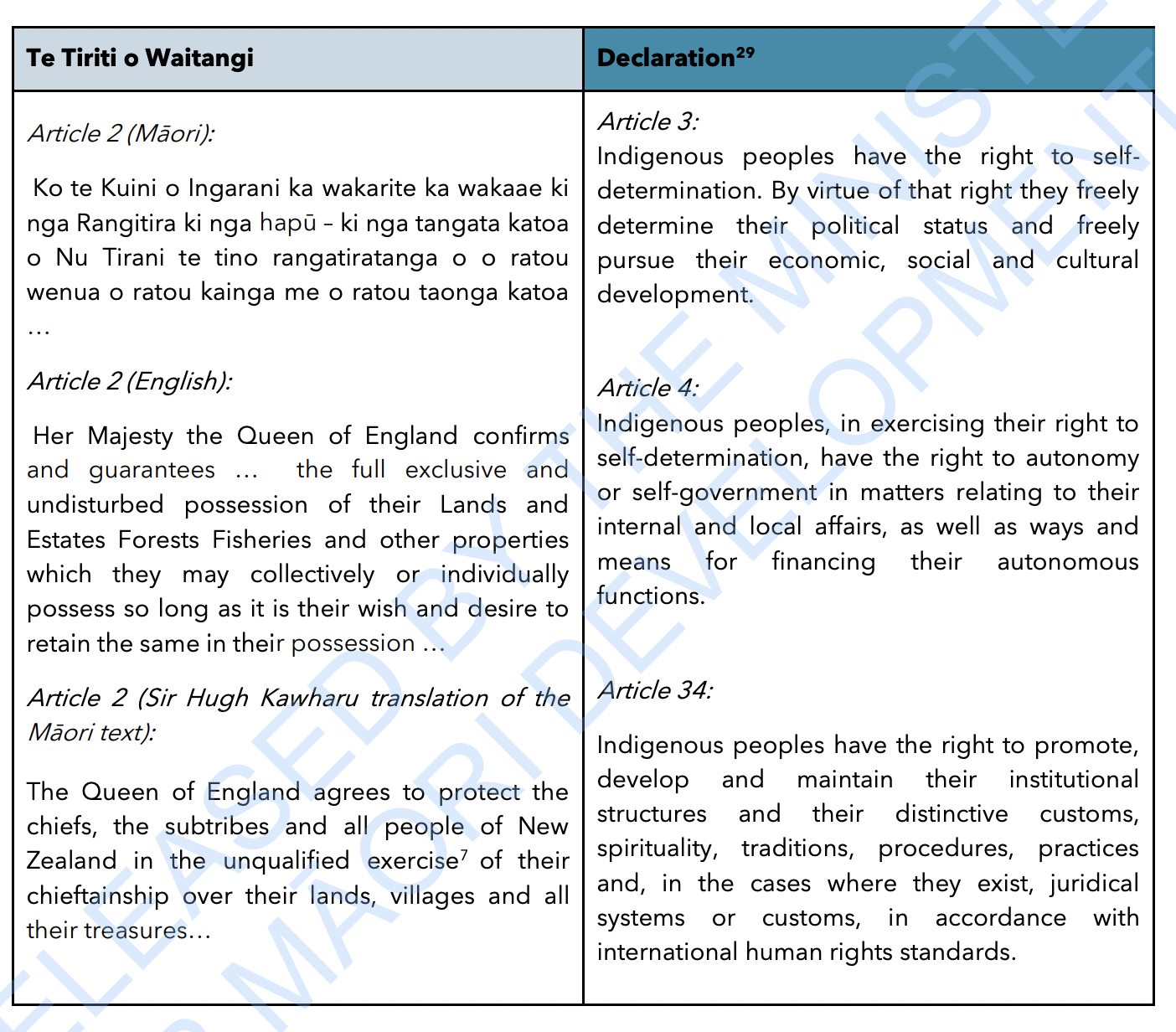

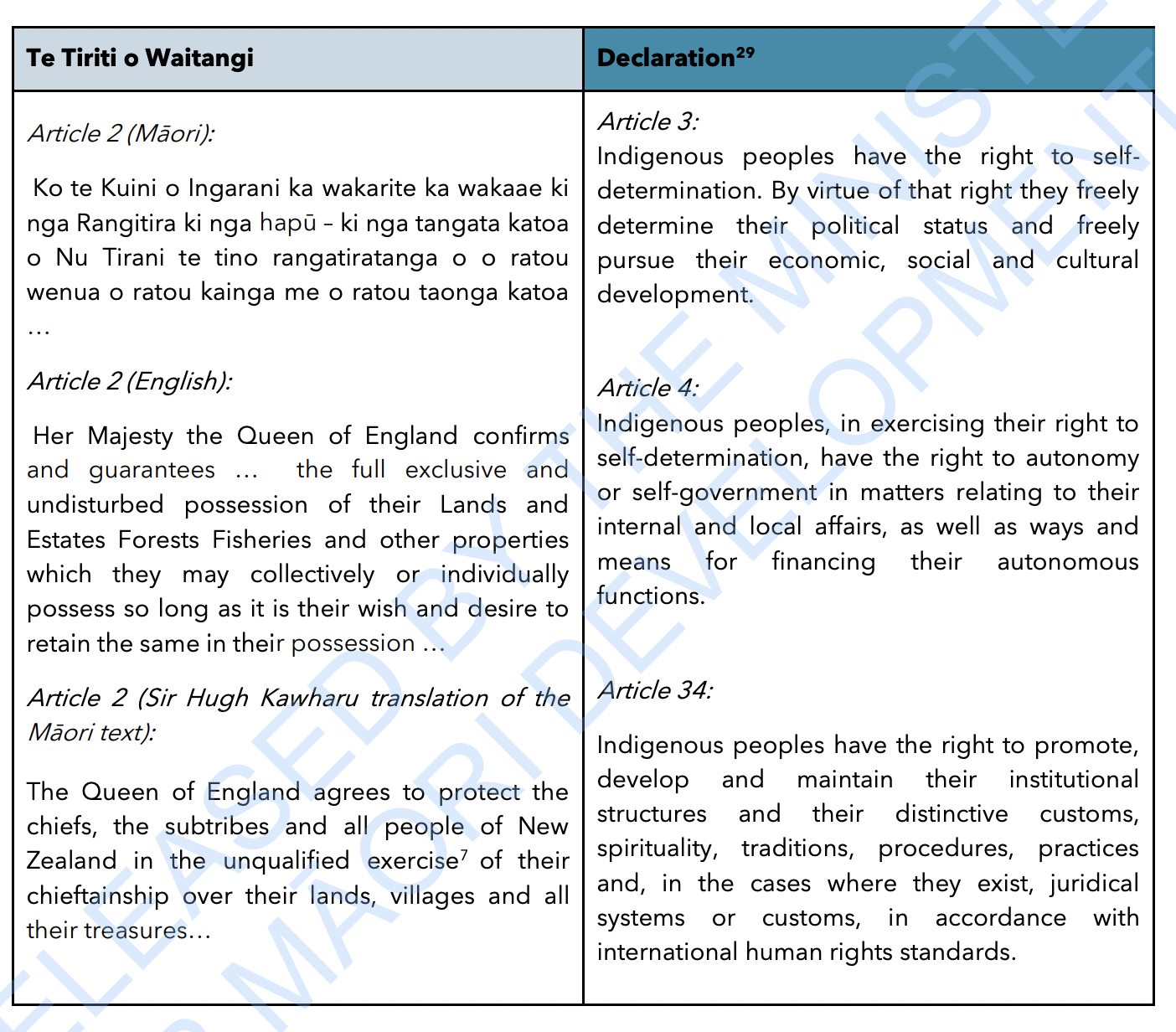

Here we will be researching into the conceptual relevance and contextual setting of who we are and where we are from by surveying our colonial history in A-NZ. This will be done by focussing on an aspect of pre-colonial society - tamaariki, and post-colonial society - Ōranga Tamariki [Formerly Child, Youth, and Family]. To understand colonisation, we first must understand what was colonised. Māori society in pre-colonial times had some distinct differences in how they worked, one of these differences is around how children were regarded, treated, raised, and educated into their adulthood. Additionally, the 'Royal Commission of Inquiry into Care' - has been a watershed moment for NZ society in our ongoing efforts to face up to the true impacts that colonisation has had and continues to have on our social world. By surveying the pre-colonial research and comparing that with our present-day findings from the commission of inquiry, we can develop a clear understanding of what colonisation has done, and what needs to be returned to the indigenous people of our land in terms of justice and honouring the commitments made in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

In the second level of our inquiry we will look at how generations of Māori scholars, activists, students, kaumatua and so on.. have relentlessly fought to maintain the survival of Māori culture and language; and, the return of Māori lands that were wrongfully and illegally confiscated over the 19th and 20th centuries.

For this section, a whakataukī that can guide our pathway is:

E tū kahikatea; Hei whakapae ururoa; Awhi mai awhi atu; Tātou tātou e Tātou tātou e

Stand tall like the tree; To brave the storms;Embrace one another; We are one together

Kimihia te mea ngaro - seek what has been lost

Success Criteria:

to relate whakataukī #1 to our colonial history.

to relate whakataukī #2 to our modern history

to relate whakataukī #3 to our present-day

Inquiries:

- Pre-colonial childrearing and education

- The Royal Commission Inquiry of Care

- The fight for land, language and mokopuna

Further Learning:

-

Kia ora taatou, our context for this term is Kia Mana Āke - which at MHJC we interpret as Growing Greatness.

Our exploration of this whakataukī is going to be directed on two levels. First, we will be aiming to situate ourselves within the study - the reasons for this are communicated in the whakataukī:

"Inā kei te mohio koe ko wai koe, i anga mai koe i hea, kei te mohio koe, kei te anga atu ki hea"If you know who you are and where you are from, then you will know where you are going

Here we will be researching into the conceptual relevance and contextual setting of who we are and where we are from by surveying our colonial history in A-NZ. This will be done by focussing on an aspect of pre-colonial society - tamaariki, and post-colonial society - Ōranga Tamariki [Formerly Child, Youth, and Family]. To understand colonisation, we first must understand what was colonised. Māori society in pre-colonial times had some distinct differences in how they worked, one of these differences is around how children were regarded, treated, raised, and educated into their adulthood. Additionally, the 'Royal Commission of Inquiry into Care' - has been a watershed moment for NZ society in our ongoing efforts to face up to the true impacts that colonisation has had and continues to have on our social world. By surveying the pre-colonial research and comparing that with our present-day findings from the commission of inquiry, we can develop a clear understanding of what colonisation has done, and what needs to be returned to the indigenous people of our land in terms of justice and honouring the commitments made in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

In the second level of our inquiry we will look at how generations of Māori scholars, activists, students, kaumatua and so on.. have relentlessly fought to maintain the survival of Māori culture and language; and, the return of Māori lands that were wrongfully and illegally confiscated over the 19th and 20th centuries.

For this section, a whakataukī that can guide our pathway is:

E tū kahikatea; Hei whakapae ururoa; Awhi mai awhi atu; Tātou tātou e Tātou tātou e

Stand tall like the tree; To brave the storms;Embrace one another; We are one together

Kimihia te mea ngaro - seek what has been lost

Success Criteria:

to relate whakataukī #1 to our colonial history.

to relate whakataukī #2 to our modern history

to relate whakataukī #3 to our present-day

Inquiries:

- Pre-colonial childrearing and education

- The Royal Commission Inquiry of Care

- The fight for land, language and mokopuna

Further Learning:

-

Kia ora taatou, our context for this term is Kia Mana Āke - which at MHJC we interpret as Growing Greatness.

Our exploration of this whakataukī is going to be directed on two levels. First, we will be aiming to situate ourselves within the study - the reasons for this are communicated in the whakataukī:

"Inā kei te mohio koe ko wai koe, i anga mai koe i hea, kei te mohio koe, kei te anga atu ki hea"If you know who you are and where you are from, then you will know where you are going

Here we will be researching into the conceptual relevance and contextual setting of who we are and where we are from by surveying our colonial history in A-NZ. This will be done by focussing on an aspect of pre-colonial society - tamaariki, and post-colonial society - Ōranga Tamariki [Formerly Child, Youth, and Family]. To understand colonisation, we first must understand what was colonised. Māori society in pre-colonial times had some distinct differences in how they worked, one of these differences is around how children were regarded, treated, raised, and educated into their adulthood. Additionally, the 'Royal Commission of Inquiry into Care' - has been a watershed moment for NZ society in our ongoing efforts to face up to the true impacts that colonisation has had and continues to have on our social world. By surveying the pre-colonial research and comparing that with our present-day findings from the commission of inquiry, we can develop a clear understanding of what colonisation has done, and what needs to be returned to the indigenous people of our land in terms of justice and honouring the commitments made in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

In the second level of our inquiry we will look at how generations of Māori scholars, activists, students, kaumatua and so on.. have relentlessly fought to maintain the survival of Māori culture and language; and, the return of Māori lands that were wrongfully and illegally confiscated over the 19th and 20th centuries.

For this section, a whakataukī that can guide our pathway is:

E tū kahikatea; Hei whakapae ururoa; Awhi mai awhi atu; Tātou tātou e Tātou tātou e

Stand tall like the tree; To brave the storms;Embrace one another; We are one together

Kimihia te mea ngaro - seek what has been lost

Success Criteria:

to relate whakataukī #1 to our colonial history.

to relate whakataukī #2 to our modern history

to relate whakataukī #3 to our present-day

Inquiries:

- Pre-colonial childrearing and education

- The Royal Commission Inquiry of Care

- The fight for land, language and mokopuna

-

Kia ora taatou, our context for this term is Kia Mana Āke - which at MHJC we interpret as Growing Greatness.

Our exploration of this whakataukī is going to be directed on two levels. First, we will be aiming to situate ourselves within the study - the reasons for this are communicated in the whakataukī:

"Inā kei te mohio koe ko wai koe, i anga mai koe i hea, kei te mohio koe, kei te anga atu ki hea"

If you know who you are and where you are from, then you will know where you are going

Here we will be researching into the conceptual relevance and contextual setting of who we are and where we are from by surveying our colonial history in A-NZ. This will be done by focussing on an aspect of pre-colonial society - tamaariki, and post-colonial society - Ōranga Tamariki [Formerly Child, Youth, and Family]. To understand colonisation, we first must understand what was colonised. Māori society in pre-colonial times had some distinct differences in how they worked, one of these differences is around how children were regarded, treated, raised, and educated into their adulthood. Additionally, the 'Royal Commission of Inquiry into Care' - has been a watershed moment for NZ society in our ongoing efforts to face up to the true impacts that colonisation has had and continues to have on our social world. By surveying the pre-colonial research and comparing that with our present-day findings from the commission of inquiry, we can develop a clear understanding of what colonisation has done, and what needs to be returned to the indigenous people of our land in terms of justice and honouring the commitments made in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

In the second level of our inquiry we will look at how generations of Māori scholars, activists, students, kaumatua and so on.. have relentlessly fought to maintain the survival of Māori culture and language; and, the return of Māori lands that were wrongfully and illegally confiscated over the 19th and 20th centuries.

For this section, a whakataukī that can guide our pathway is:

E tū kahikatea; Hei whakapae ururoa; Awhi mai awhi atu; Tātou tātou e Tātou tātou e

Stand tall like the tree; To brave the storms;Embrace one another; We are one together

Kimihia te mea ngaro - seek what has been lost

Success Criteria:

to relate whakataukī #1 to our colonial history.

to relate whakataukī #2 to our modern history

to relate whakataukī #3 to our present-day

Inquiries:

- Pre-colonial childrearing and education

- The Royal Commission Inquiry of Care

- The fight for land, language and mokopuna