9F1 Global Studies

Section outline

-

Tena koutou katoa, welcome to term 1 of our Year 9 Global Studies in 2021. Our learning context this term is built around the idea of: ‘Kōkōkaha’ – Powered by Wind (Sail Away) This idea can be understood in the following Māori proverb: He Whakataukī: “Ko te pae tawhiti, whāia kia tata; ko te pae tata, whakamaua kia tīna”

Metaphorical: Seek out distant horizons and cherish those you attain

Literal: Strive to attain that which is out of your reach & make plans to

achieve it. Goal setting & the power of envisioning + planning for a better future

In Global Studies we will explore this learning context by looking at the relationship between the peoples of Tamaki-Makaurau (Auckland) and the bodies of water we are surrounded by in the Hauraki Gulf (Tikapa Moana) and the Manukau Harbour (Te Manuka).

Currently, the America’s Cup is being hosted in our waters and this event fits into a long tradition of sailing, navigation, and innovation being upon our waters in Tamaki-Makaurau. We will use this as a launch-pad to interrogate a rich and important history which we are now part of in 2021.

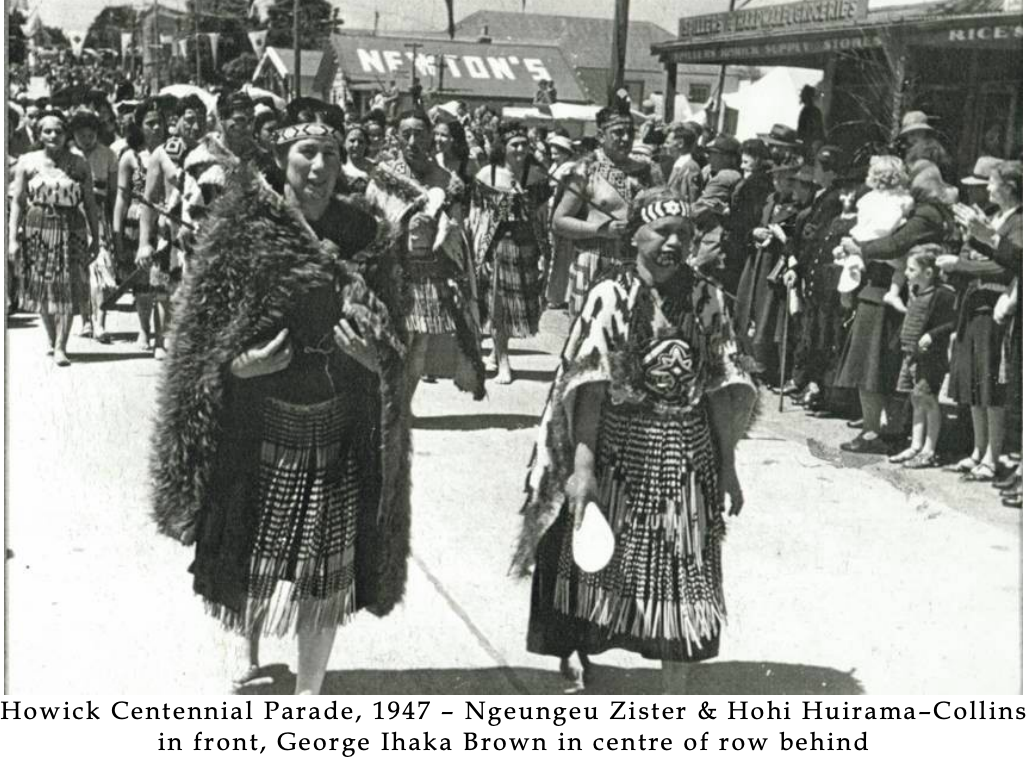

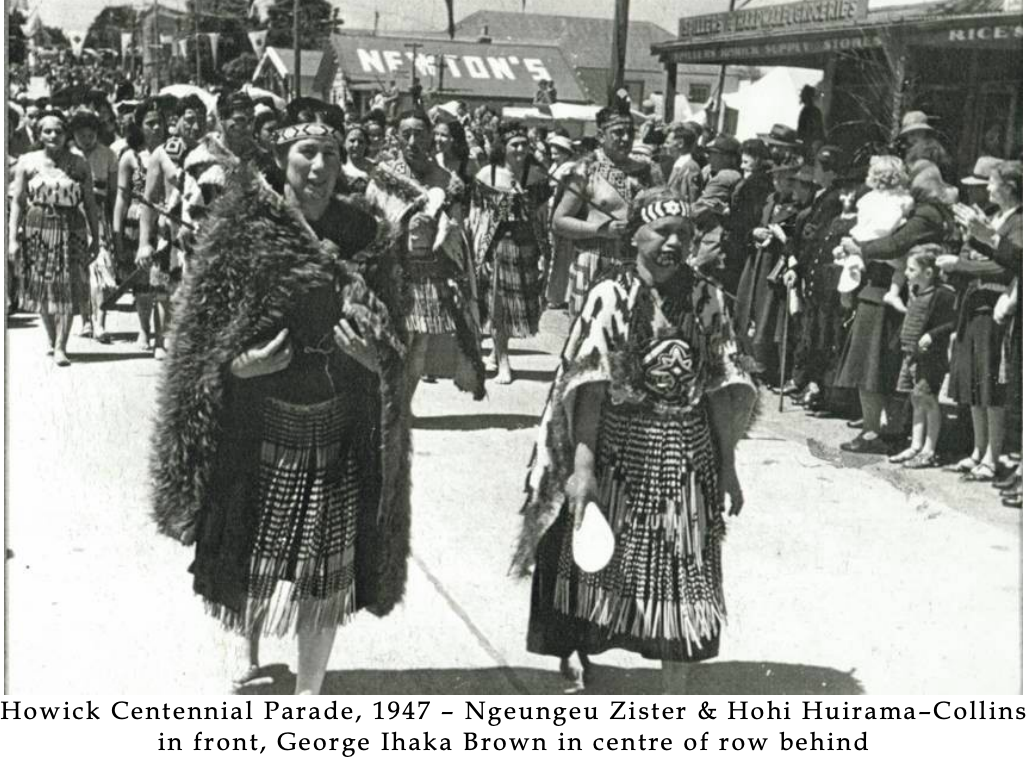

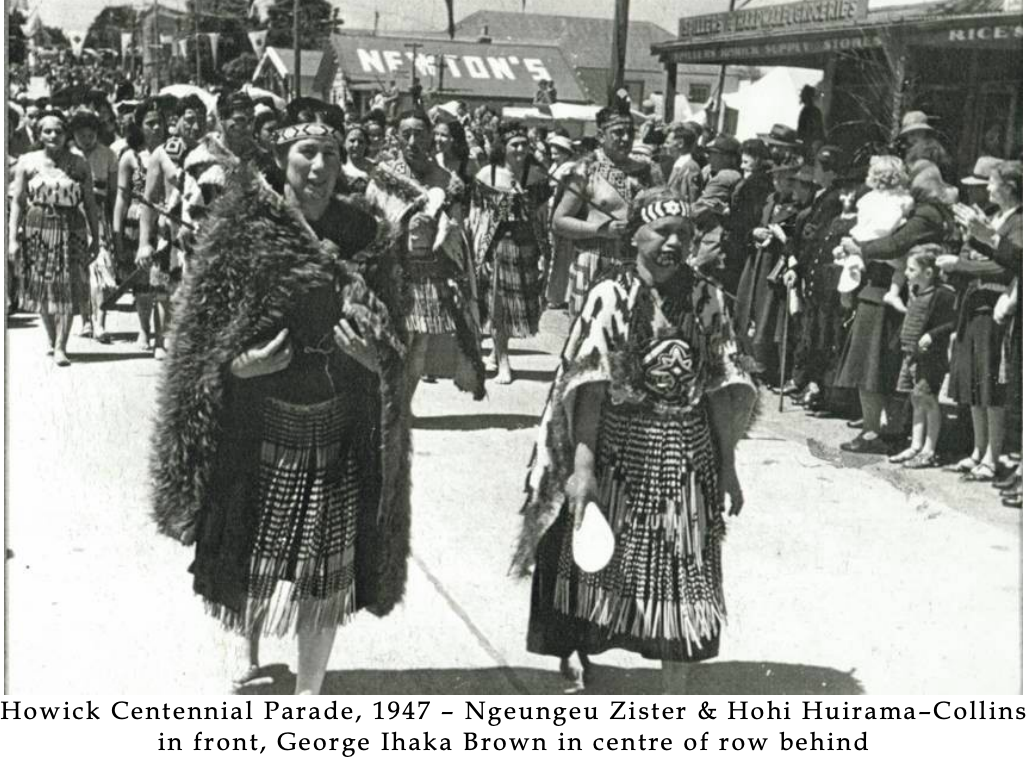

We will begin with looking at the innovation of waka hourua and how they whakapapa to the modern craft we observe today. By surveying the voyage of Kupe & Kuramarotini in circa 950CE, to Toitehuatahi in the early 12th century; and then the arrival of Tainui and Te Arawa in 1350CE; to James Cook’s arrival in 1769; to the Hokulea’s arrival in 1985; then Sir Peter Blake’s successful defence in 2000; up to the present day events that are taking place.

In preparation for our first trip to the Maritime Museum, we will spend our first section of study this term interrogating the migration from Polynesia/Tahiti to Aotearoa. This week we will be exploring the history of Kupe and Kuramarotini, & their discovery of Aotearoa New Zealand; and we will survey the history of Toitehuatahi’s journey in 1150CE. Our first task will be to interrogate the Purākau of Maui and Tama-nui-te-ra, using insights from Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, in order to decode the knowledge or matauranga contained in this account.

We are learning to….

Conceptualise the scale of the challenges faced by early Polynesian navigators; and, to develop an understanding of the methods by which these challenges were addressed.

I am able to….

Describe and explain the discovery of Aotearoa New Zealand by using reliable sources of information.

Homework:

From the youtube clip below:

Recall 3 pieces of key information from each clip

Form 2 research questions that you can use as a pathway for further research

Create 1 Insight by reflecting on what you learn in the clip & what you know already about the things discussed

-

We will next move to explore the journey taken by the Tainui waka and how this journey intersects with us here in Owairoa.

We will first be exploring the journey of the Tainui waka through the Tamaki Isthmus and down to Kawhia;

then, we will do a case study of the pa known as Whakakaiwhara, where the Tainui anchored around 1350ce.

Finally, we will survey the Tainui connections with our local iwi of Ngāi Tai Ki Tamaki and Ngāti Paoa by learning the origin histories of these tribes.

LO's We are learning to...

- integrate knowledge of the significance of Tainui histories in our nation's identity.

- develop our understanding of how the histories of Tainui are significant to our local communities present-day identity.

- associate ourselves with the histories of Ngāi Tai ki Tamaki & Ngāti Paoa in our local communities story about itself.

SC's I can now...

- Place the significance of Tainui and the iwi associated to it in a broad historical context.

-

LO's We are learning to...

- integrate knowledge of the significance of Tainui histories in our nation's identity.

- develop our understanding of how the histories of Tainui are significant to our local communities present-day identity.

- associate ourselves with the histories of Ngāi Tai ki Tamaki & Ngāti Paoa in our local communities story about itself.

SC's I can now...

- Place the significance of Tainui and the iwi associated to it in a broad historical context.

-

We will next move to explore the journey taken by the Tainui waka and how this journey intersects with us here in Owairoa.

We will first be exploring the journey of the Tainui waka through the Tamaki Isthmus and down to Kawhia;

then, we will do a case study of the pa known as Whakakaiwhara, where the Tainui anchored around 1350ce.

Finally, we will survey the Tainui connections with our local iwi of Ngāi Tai Ki Tamaki and Ngāti Paoa by learning the origin histories of these tribes.

LO's We are learning to...

- integrate knowledge of the significance of Tainui histories in our nation's identity.

- develop our understanding of how the histories of Tainui are significant to our local communities present-day identity.

- associate ourselves with the histories of Ngāi Tai ki Tamaki & Ngāti Paoa in our local communities story about itself.

SC's I can now...

- Place the significance of Tainui and the iwi associated to it in a broad historical context.

-

We will next move to explore the journey taken by the Tainui waka and how this journey intersects with us here in Owairoa.

We will first be exploring the journey of the Tainui waka through the Tamaki Isthmus and down to Kawhia;

then, we will do a case study of the pa known as Whakakaiwhara, where the Tainui anchored around 1350ce.

Finally, we will survey the Tainui connections with our local iwi of Ngāi Tai Ki Tamaki and Ngāti Paoa by learning the origin histories of these tribes.

LO's We are learning to...

- integrate knowledge of the significance of Tainui histories in our nation's identity.

- develop our understanding of how the histories of Tainui are significant to our local communities present-day identity.

- associate ourselves with the histories of Ngāi Tai ki Tamaki & Ngāti Paoa in our local communities story about itself.

SC's I can now...

- Place the significance of Tainui and the iwi associated to it in a broad historical context.

-

Kia ora tātou,

Nau mai, haere mai; welcome back for term 2 of Global Studies for 2021.

Our learning context this term is Ngā Pukenga Hou which I understand as engaging new skills.

There are 2 big ideas in the background of our studies this term - but we will focus on one at a time. These ideas are:

1. Developing our understanding of how the ideas and actions of people in the past have had a significant impact on people’s lives.

2. How the Treaty of Waitangi is responded to differently by people in different times and places.

In Global Studies, we are using these big ideas as a general path to follow; the destination we are aiming for is to deepen our understanding of the learning context in connection with a new set of skills to learn.

In social sciences there are many, many skills you can learn; from constructing a logical argument to the ability to communicate effectively, to taking political action, to creating impactful art (like the Banksy piece below), or community organising and activism to name only a few; and learning them is a lifelong journey.

One of the most important skills for young people in 2021 is having an understanding of activism and taking action. With this in mind, we will examine how youth activists have used specific skills to successfully change the world for the better.

The learning strategy we will engage to connect with this skill-based context has been planned out using the student-voice team's input from last term as a guide; and their ideas has shaped the potential learning pathways we will pursue during this term. So, what's on the schedule?

We will complete two case studies this term, both of which will assist us to conceptualise activism in detail so as to be able to explore and then reflect on the skills and knowledge that appear useful to becoming a successful activist and change-maker..

The first case study interrogates a case from the global community that took pace in 2016 in the USA (DAPL/Standing Rock); and, the second case we will discuss is a local one; where activists occupied the place to protect Māori land in 1977/1978 (Takaparawhā/Bastion Point).

In the second study, we will have a chance to briefly explore some of the pre-European histories of Tāmaki Makaurau and the iwi of Ngāti Whātua.

Then, we will move to concentrate on the establishing of Auckland in 1840; and next we will briefly inspect the confiscation of Ngāti Whātua lands between 1840-1970; and finally we will conduct a social inquiry into the issues which led to the 506 day occupation by activists in 1977/1978.

To reflect on our term's learning we will consider ways in which we might conceptualise a realistic plan to use our newly polished activism skills to assist the iwi of Ngāti Paoa who are currently occupying their wahi tapu (sacred places) on Waiheke Island; the reason they are protesting is because the ultra-rich (who do not live on Waiheke) want to build a marina to dock their yachts in the weekend.

However, before we can accomplish any of this investigative research, inquiry learning, or critical reflection; we first must understand the historical context of the cases we study. The context of Colonisation must always be examined in relation to its history; because, the current nature of our society is always being shaped by people who came before us, just as we will shape society for those who come after us. This is important to remember when considering colonisation - much of present-day colonisation is the result of laws and ideas that were already a part of society before we got here.

Thus brings us to the first section of learning that we will engage with.

We will attempt to answer the question "How did this whole colonisation process even happen in the first place?"

To address this question we need to go all the way back to the 15th century (1400's) and interrogate some key moments in history that led to the social conditions that motivate the activism we will examine in our case studies.

In the first 2-3 weeks we will cover:

The Doctrine of Discovery

The Origins of Racism

The History of Slavery and Colonisation

The Consequences of Greed

WALT...

- Explain the root causes and historical events that caused the original process of colonisation to begin.

- Connect key moments in history to present-day issues in a logical argument.

- Identify and define the key concept-words we will use to examine different perspectives in our case studies.

By learning this I will be able to...

- explain what colonisation is using key social studies concepts

- name and describe pivotal moments in the history of colonisation as logically connected.

- apply specific concepts to examine how different perspectives may view the same history in completely different terms.

Home-research: James Cook and the Doctrine of Discovery

1. The Doctrine of Discovery provided a framework for Christian explorers to do what?

2. What term did Lieutenant William Hobson use to declare Te Waipounamu as 'empty land' in 1840 and what did this mean for the Māori people living there?

3. What are the "despicable assumptions" about indigenous peoples that the United Nations Forum says were encouraged by the Doctrine of Discovery?

4. What is the simple answer for why every NZ government for the past 180 years has been allowed to break the promises made and ignore the responsibilities they have to Māori under Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi?

Extra for Experts

ReDiscovering History, this week: Historian Vincent O'Malley discusses Dispossession & the Settlement Act

December 3, 1863; Governor George Grey signed into law the New Zealand Settlements Act.

It’s a piece of legislation that had devastating consequences for many Māori communities. The Settlements Act provided the primary legal justification for raupatu — huge confiscations of Māori land that were done to punish acts of “rebellion” by Māori leaders. It declared that where “any Native Tribe or Section of a Tribe or any considerable number thereof” had committed acts of “rebellion against Her Majesty’s authority” since January 1, 1863, their lands could be declared subject to the Act and seized for the purposes of settlement. It was passed into law by the all-Pākehā parliament to strategically crush Māori independence.

Governor George Grey

Grey and his ministers had drawn up these confiscation plans before invading Waikato in July 1863 and, by August, had begun recruiting military settlers who were to be offered a portion of the seized lands in return for their services. Confiscation wasn’t an afterthought or a response to Māori actions, but an important part of the overall invasion plans. The presence of military settlers on a portion of the seized lands would ensure the conquest of these was made permanent, while the sale of the remainder on the open market would pay for the whole scheme. Māori would effectively pay the costs of living on the land they had always lived on twice-over; and, they were paying the people who had only just arrived!

The war was entered into with deep roots in British imperial practice, in other words - trickery, deception and dishonourable conduct wasn't wrong as far as the British were concerned. Only the "native savages" were silly enough to be honest and sincere with their words and the Māori weakness was that they saw warfare as operating on the honour (or mana) of the people who chose to fight - no Pākehā child was killed in combat by Māori warriors - but, many Māori children were slaughtered by the colonial troops.

A similar scheme of plantation had been used in 17th-century Ireland. Ironically, many of the troops brought to New Zealand to fight these wars of conquest for the Crown centuries later were Irish Catholics whose own communities had suffered exactly the same fate. Victims of imperialism in this way became its perpetrators.

Henry Sewell believed the Settlement Act worked exactly how the creators of the policy wanted it to. It was intended to drive even more Māori to offer resistance; once they resisted paying double for land they already owned, the Settlement Act allowed the lands to be seized by the settler-government and sold as punishment for these acts of “rebellion” (of not paying double for land they had always lived on).

In all, more than 3.4 million acres of land was confiscated under the Settlements Act across many districts — in Waikato, Taranaki, Tauranga, eastern Bay of Plenty, and Mohaka-Waikare.

Further lands were “ceded” to the Crown at Tūranga, Wairoa, and Waikaremoana under a distinct confiscation regime covering the East Coast region.

Despite repeated promises that Māori who didn’t take up arms against the Crown would have their lands guaranteed to them in full, confiscation was applied to all Māori whether they were loyal to the British or not. And it even took in areas owned by those who had fought on the government side.

The New Zealand Settlements Act 1863.

Fearing that sweeping and excessive confiscations would only encourage more Māori resistance and as a result increase the military and financial cost for British taxpayers, the British settler-government introduced a range of restrictions on how the Settlements Act would be implemented. Most of these were ignored. Rather than trying to stop what they knew was a gross injustice, ministers in London washed their hands of the matter, concerned only with how soon they could withdraw their troops from New Zealand. Many of those soldiers, including their commander, Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron, had become increasingly annoyed with what they were being asked to do, and began to query why they should fight a war of conquest and dispossession for the benefit of New Zealand settlers.

The 1863 Act was clear that lands could only be confiscated if they were eligible sites for settlement. But so wholesale were the takings that mountains, hills, lakes, swamps and other sites were included. Vast areas that had been confiscated remained unsettled and unsold. Many of these lands still form part of the Crown estate today. In the Waikato, Auckland speculators such as Thomas Russell and Frederick Whitaker, leading proponents of the confiscation policy as members of government in 1863, personally acquired many of these lands. Once land prices recovered, they stood to make enormous profits from their investments.

Through the two decades after 1840, Māori were in many ways the leading drivers of New Zealand’s economy, producing much of its export income, while also feeding hungry settlers in Auckland and other towns. That economic infrastructure was destroyed almost literally overnight as cattle and crops were seized or destroyed, flour mills and homes in many cases torched, and the lands that had been key to this wealth confiscated. The Māori economy was delivered a near fatal blow. That was not something that could be easily or quickly overcome. Generations of Māori were forced into lives of landlessness and poverty. In many ways, we still live with the legacy of the New Zealand Settlements Act today. Treaty settlements have helped to repair some of the damage done to the Tangata Whenua of this nation (Māori), and allowed them to again become major players in the New Zealand economy. But, given that these settlements typically represent no more than about one or two percent of the unimproved value of the lands that were taken, they are never going to fully compensate for all that was lost. Many Pākehā have little idea of this history or how it continues to reverberate. That’s hardly surprising, given how few people learn anything about it at school. It’s time to do something about that. It’s time we as a nation owned up to our past. That’s bigger than Treaty settlements. It’s about dialogue and mutual understanding. And that’s why the story of the New Zealand Settlements Act should be more widely known. It is a dark tale of dispossession and colonial greed whose consequences are still felt today.

excerpt from Vincent O'Malley, https://e-tangata.co.nz/history/a-dark-tale-of-dispossession-and-greed/

-

To address this question we need to go all the way back to the 15th century (1400's) and interrogate some key moments in history that led to the social conditions that motivate the activism we will examine in our case studies.

In the first 2-3 weeks we will cover:

The Doctrine of Discovery

The Origins of Racism

The History of Slavery and Colonisation

The Consequences of Greed

WALT...

- Explain the root causes and historical events that caused the original process of colonisation to begin.

- Connect key moments in history to present-day issues in a logical argument.

- Identify and define the key concept-words we will use to examine different perspectives in our case studies.

By learning this I will be able to...

- explain what colonisation is using key social studies concepts

- name and describe pivotal moments in the history of colonisation as logically connected.

- apply specific concepts to examine how different perspectives may view the same history in completely different terms.

-

Nau mai, haere mai i wiki toru

-

- We are exploring relationships between specific iwi-Māori beliefs/philosophies of kaitiakitanga,whakapapa, and mātauranga/mātauranga-a-iwi

- We are exploring some ideas, beliefs, and concepts that some iwi use to make sense of how Māori relate to the natural world.

- We are exploring how our diverse communities can establish a deeper connection and understanding of ourselves and others through our shared relationship to nature.

-

- We are exploring relationships between specific iwi-Māori beliefs/philosophies of kaitiakitanga,whakapapa, and mātauranga/mātauranga-a-iwi

- We are exploring some ideas, beliefs, and concepts that some iwi use to make sense of how Māori relate to the natural world.

- We are exploring how our diverse communities can establish a deeper connection and understanding of ourselves and others through our shared relationship to nature.

-

- We are exploring relationships between specific iwi-Māori beliefs/philosophies of kaitiakitanga,whakapapa, and mātauranga/mātauranga-a-iwi

- We are exploring some ideas, beliefs, and concepts that some iwi use to make sense of how Māori relate to the natural world.

- We are exploring how our diverse communities can establish a deeper connection and understanding of ourselves and others through our shared relationship to nature.

-

- We are exploring relationships between specific iwi-Māori beliefs/philosophies of kaitiakitanga,whakapapa, and mātauranga/mātauranga-a-iwi

- We are exploring some ideas, beliefs, and concepts that some iwi use to make sense of how Māori relate to the natural world.

- We are exploring how our diverse communities can establish a deeper connection and understanding of ourselves and others through our shared relationship to nature.

-

- We are exploring relationships between specific iwi-Māori beliefs/philosophies of kaitiakitanga,whakapapa, and mātauranga/mātauranga-a-iwi

- We are exploring some ideas, beliefs, and concepts that some iwi use to make sense of how Māori relate to the natural world.

- We are exploring how our diverse communities can establish a deeper connection and understanding of ourselves and others through our shared relationship to nature.

-

- We are exploring relationships between specific iwi-Māori beliefs/philosophies of kaitiakitanga,whakapapa, and mātauranga/mātauranga-a-iwi

- We are exploring some ideas, beliefs, and concepts that some iwi use to make sense of how Māori relate to the natural world.

- We are exploring how our diverse communities can establish a deeper connection and understanding of ourselves and others through our shared relationship to nature.

-

- We are exploring relationships between specific iwi-Māori beliefs/philosophies of kaitiakitanga,whakapapa, and mātauranga/mātauranga-a-iwi

- We are exploring some ideas, beliefs, and concepts that some iwi use to make sense of how Māori relate to the natural world.

- We are exploring how our diverse communities can establish a deeper connection and understanding of ourselves and others through our shared relationship to nature.

-

- We are exploring relationships between specific iwi-Māori beliefs/philosophies of kaitiakitanga,whakapapa, and mātauranga/mātauranga-a-iwi

- We are exploring some ideas, beliefs, and concepts that some iwi use to make sense of how Māori relate to the natural world.

- We are exploring how our diverse communities can establish a deeper connection and understanding of ourselves and others through our shared relationship to nature.

-

-