9C2 Global Studies

Section outline

-

Nau mai, Haere mai; welcome to Global Studies 2020. This year you are transitioning from the junior school version of social studies into the high school curriculum of social scholarship.

Kia ora...

Success Criteria: I can/have...

- understand the purpose, importance, & application of concepts in social scholarship

- recognise how a person's identity shapes their perspective, and why this is unavoidable when analysing politics and society

Activities:

- see google classroom

The buzz:

My aim for this year is to provide you all with the skills and understandings you need to be capable of applying your own perspective, and value system, to any social topic and/or content effectively, and independently - I will not be “teaching you topics”.I aim to teach you how to have your own thoughts about topics, and how to present those thoughts in a persuasive and effective manner. The problem is, if I teach you all about a select ‘topic’ per se, however i present that part of society or history cannot avoid being tainted by my ideological perspective, and ethical values.

This is the hardest part about social studies/global studies to accept; that there is never any certainty of truth when it concerns society, people cannot be calculated using a neat pythagorean theorem. The way we each individually see our society cannot ever claim to be absolutely right about what it is or should be, but equally we never have to accept that we’re wrong without good reasons either, what we each value and prioritise in life is shaped by the perspective we hold.

It is getting our heads around this idea that we will tackle first. Then, we can move onto to our study of Colonialism and Imperialism wherein we will begin by looking at their global significance in world history. Gradually we will journey back to Aotearoa in order to deepen our understanding of Treaty of Waitangi in terms of social scholarship; by applying the conceptual tools we discover regarding Colonialism & Imperialism - thus far your knowledge of the Treaty will likely be in terms of knowing some dates, maybe a few names, locations, facts; but, now you are beginning to contextualise and evaluate the place of the Treaty in modern NZ society.

Before we can embark on that journey though, we must first understand:

how a person's identity shapes their perspective;

and, how a perspective shapes the point someone makes and how they view the significance of the facts they discover;

which influences the reasons they use to justify their point;

a point that is only verified by providing credible sources

And, how concepts are the glue that holds these steps of analysis together.

-

Kia ora...9C2

Overview:

Colonialism & Imperialism: a study of various perspectives throughout time

At least since the Crusades (1095 CE - 1270 CE) and the conquest of the Americas (1492 - 1800), political theorists have struggled with the difficulty of finding agreement where our ideas about justice and natural law meet with the practice of European sovereignty over non-Western peoples. In the nineteenth century, the tension between liberal thought and colonial practice became particularly acute, as dominion of Europe over the rest of the world reached its peak.

Like colonialism, imperialism also involves political and economic control over a dependent territory.

Colonialism is not a modern feature of World history, examples of one society gradually expanding their control over neighbouring territories and re-settling its people on the newly conquered territory. The ancient Greeks set up colonies as did the Romans, the Moors, and the Ottomans, to name just a few of the most famous examples.

Colonialism, then, has no specific time or place. The difficulty of defining colonialism stems from the fact that the term is often used as a synonym for imperialism. Both colonialism and imperialism were forms of conquest that were expected to benefit Europe economically and strategically.

The term imperialism often describes cases in which a foreign government administers a territory without significant settlement;

Our Learning Context: He waka eke nona - Turangawaewae (stomping ground/place to stand)

Our inquiry this week will provide a gateway into our context in terms of the conceptual interpretation of the whakatauki

we are working with. A place to stand, or turangawaewae, is an important aspect of the system of values within

Te Ao Maori (the Maori world). Yet, it is not solely the rapunga whakaaro (philosophy) of Maori people. The idea of having

'a place to stand' is of global significance, especially in relation to the history of Colonialism and Imperialism. We will explore and reflect

upon the Colonisation histories of the African Continent, China, India, America, and finally we will return to Aotearoa for a case study. This

term we are aiming to compare and contrast the experiences of Colonialism around the world, with the experiences of Colonialism in NZ.

Success Criteria: I can/have...- record high quality notes from presentations using a specific strategy for note-taking.

- list multiple perspectives and what they emphasise in the analyses they give regarding colonialism and/or imperialism.

- recognise the motivations for various imperial powers to create the "Scramble for Africa"

- connect the colonial history of Africa (from the 16th century) logically, to the modern day struggles faced in many African nations.

- reflect on how the colonial histories of Aotearoa, New Zealand & the African continent have key differences worth comparing in an analysis.

Activities

See Google classroom:

Welcome to the Scramble for Africa! You will take on the role of a European country ready to colonize the continent of Africa. Your goal is to claim as much land and as many resources as possible, though your specific objectives will vary. All of the rules you need to play are built into the game – good luck!

Homework Policy:Students are NOT obligated to complete ANY homework in Global Studies in 9C2, it is your personal choice to self-regulate your learning this year. I will, of course, provide opportunities for you to engage with a variety of learning strategies in class. This independence will to allow you to experiment with time management strategies, which is a lifelong skill you need to be equipped with for your educational future. However, if you are wanting more work; either ask me for extension learning, or you are always welcome to work on classwork at home.

Academic evidence for the value of minimising homework in Junior College:

https://www.healthline.com/health-news/children-more-homework-means-more-stress-031114#3

-

Kia ora...9C2

Overview:

Colonialism & Imperialism: a study of various perspectives throughout time

At least since the Crusades (1095 CE - 1270 CE) and the conquest of the Americas (1492 - 1800), political theorists have struggled with the difficulty of finding agreement where our ideas about justice and natural law meet with the practice of European sovereignty over non-Western peoples. In the nineteenth century, the tension between liberal thought and colonial practice became particularly acute, as dominion of Europe over the rest of the world reached its peak.

Like colonialism, imperialism also involves political and economic control over a dependent territory.

Colonialism is not a modern feature of World history, examples of one society gradually expanding their control over neighbouring territories and re-settling its people on the newly conquered territory. The ancient Greeks set up colonies as did the Romans, the Moors, and the Ottomans, to name just a few of the most famous examples.

Colonialism, then, has no specific time or place. The difficulty of defining colonialism stems from the fact that the term is often used as a synonym for imperialism. Both colonialism and imperialism were forms of conquest that were expected to benefit Europe economically and strategically.

The term imperialism often describes cases in which a foreign government administers a territory without significant settlement;

Our Learning Context: He waka eke nona - Turangawaewae (stomping ground/place to stand)

Our inquiry this week will provide a gateway into our context in terms of the conceptual interpretation of the whakatauki

we are working with. A place to stand, or turangawaewae, is an important aspect of the system of values within

Te Ao Maori (the Maori world). Yet, it is not solely the rapunga whakaaro (philosophy) of Maori people. The idea of having

'a place to stand' is of global significance, especially in relation to the history of Colonialism and Imperialism. We will explore and reflect

upon the Colonisation histories of the African Continent, China, India, America, and finally we will return to Aotearoa for a case study. This

term we are aiming to compare and contrast the experiences of Colonialism around the world, with the experiences of Colonialism in NZ.

Success Criteria: I can/have...- record high quality notes from presentations using a specific strategy for note-taking.

- list multiple perspectives and what they emphasise in the analyses they give regarding colonialism and/or imperialism.

- recognise the motivations for various imperial powers to create the "Scramble for Africa"

- connect the colonial history of Africa (from the 16th century) logically, to the modern day struggles faced in many African nations.

- reflect on how the colonial histories of Aotearoa, New Zealand & the African continent have key differences worth comparing in an analysis.

Activities

See Google classroom:

Welcome to the Scramble for Africa! You will take on the role of a European country ready to colonize the continent of Africa. Your goal is to claim as much land and as many resources as possible, though your specific objectives will vary. All of the rules you need to play are built into the game – good luck!

Homework Policy:Students are NOT obligated to complete ANY homework in Global Studies in 9C2, it is your personal choice to self-regulate your learning this year. I will, of course, provide opportunities for you to engage with a variety of learning strategies in class. This independence will to allow you to experiment with time management strategies, which is a lifelong skill you need to be equipped with for your educational future. However, if you are wanting more work; either ask me for extension learning, or you are always welcome to work on classwork at home.

Academic evidence for the value of minimising homework in Junior College:

https://www.healthline.com/health-news/children-more-homework-means-more-stress-031114#3

-

Decolonization Is for Everyone

“This history is not your fault, but it is absolutely your responsibility.” A history of colonization exists and persists all around us. Nikki discusses what colonization looks like and how it can be addressed through decolonization. An equitable and just future depends on the courage we show today. “Let’s make our grandchildren proud”

-

This week will provide you with in-class guidance for your upcoming assessment.

-

Holidays brought forward, 28th March - April 15th.

-

Kia ora 9C2,

Welcome back to term 2. We hope that you have been able to relax and recharge your energy levels. It certainly wasn’t the holiday we would have liked, but we trust that you were playing your part in the fight against Covid 19 and supporting New Zealand by staying at home.

As we begin to refocus our attention on learning, there is no doubt that the start of this term will be different. We will all be learning together how to best manage learning time; while balancing it with time to stay healthy, time with family, and time to care for and stay in contact with others. We recognise that not everything we would normally do in the classroom can be replicated online. However this will be a time to learn new forms of critical thinking, communication and collaboration skills.Success Criteria: I can/have...

- Explored the Colonial history of Aotearoa, New Zealand and how different cultures/peoples have interacted throughout that history.

Activities:

- Distance Learning Projects on google classroom - https://classroom.google.com/u/0/w/NTAzODMxOTA5NjJa/t/all

-

Kia ora 9C2,

Welcome back to term 2. We hope that you have been able to relax and recharge your energy levels. It certainly wasn’t the holiday we would have liked, but we trust that you were playing your part in the fight against Covid 19 and supporting New Zealand by staying at home.

As we begin to refocus our attention on learning, there is no doubt that the start of this term will be different. We will all be learning together how to best manage learning time; while balancing it with time to stay healthy, time with family, and time to care for and stay in contact with others. We recognise that not everything we would normally do in the classroom can be replicated online. However this will be a time to learn new forms of critical thinking, communication and collaboration skills.Success Criteria: I can/have...

- Explored the Colonial history of Aotearoa, New Zealand and how different cultures/peoples have interacted throughout that history.

Activities:

- Distance Learning Projects on google classroom

-

Kia ora...9C2

If you are yet to finish at least 3 distance learning projects, then please continue on with these. If you have completed 3 or more distance learning projects, then you are ready for next steps.

The final project for this learning context requires you to undertake an inquiry project related to the distance learning tasks you have already completed. Please read the task instructions in the document carefully, make sure you have accounted for each part of the the checklist, and take your time so as to produce a quality product that reflects your learning.

Your first step is to reflect upon the distance learning projects you have completed thus far, reviewing sections that especially interested you. Select a section of learning from one of your projects that you would like to investigate further and develop an inquiry question related to that section. Your inquiry question must be open-ended and should allow you to engage with a variety of information sources.

I am available to answer any questions you may have; please turn in & list completed projects below so I can mark them and provide feedback on your learning. Also, remember to complete your learning reflection log after you have completed your brochure.Distance learning options to work on are as follows:

#1 NZ wars

#2 King movement

#3"Radicals"

#4 The battle of Ruapekapeka

#5 Voting rights in Colonial NZ

If you have completed at least 3 projects:

- Global Brochure project: final context task - due Friday. -

Kia ora...9C2

If you are yet to finish at least 3 distance learning projects, then please continue on with these. If you have completed 3 or more distance learning projects, then you are ready for next steps.

The final project for this learning context requires you to undertake an inquiry project related to the distance learning tasks you have already completed. Please read the task instructions in the document carefully, make sure you have accounted for each part of the the checklist, and take your time so as to produce a quality product that reflects your learning.

Your first step is to reflect upon the distance learning projects you have completed thus far, reviewing sections that especially interested you. Select a section of learning from one of your projects that you would like to investigate further and develop an inquiry question related to that section. Your inquiry question must be open-ended and should allow you to engage with a variety of information sources.

I am available to answer any questions you may have; please turn in & list completed projects below so I can mark them and provide feedback on your learning. Also, remember to complete your learning reflection log after you have completed your brochure.Distance learning options to work on are as follows:

#1 NZ wars

#2 King movement

#3"Radicals"

#4 The battle of Ruapekapeka

#5 Voting rights in Colonial NZ

If you have completed at least 3 projects:

- Global Brochure project: final context task - due Friday. -

Kia ora...In anticipation of our return next week, this week is dedicated to completing our critical thinking course on Education Perfect so as to develop the skills we will apply in our new learning context.

Additionally, there is a distance learning project for you to work on, this will be due Friday 24 May.

Success Criteria: I can/have...

- Define critical thinking

- Think critically about my learning

Activities:

- Education Perfect

- Distance learning project: Economic World

-

Kia ora tatou,

This week we will finish off any outstanding distance learning tasks. We are aiming to end the week with a clean slate of completed learning in preparation for our excursion into our next learning context.

All tasks are either on google classroom or Education Perfect.

If you complete all tasks before the end of the week. please see me for next learning steps.

-

Kia ora...for the next two weeks we will be coming to terms with the foundational concepts required to develop our understanding of the Economic world. It is an introduction to economics. We will first learn the content of some key concepts, and then move to apply these concepts in an economic analysis.

As a novice, economics seems to be a dry social science that is laced with diagrams and statistics; a complex branch that deals with rational choices by an individual as well as nations — a branch of study which does not befit isolated study but delving into the depths of other subject areas (such as psychology and world politics).

What is Economics?

Economics Definition: Economics is essentially a study of the usage of resources under specific constraints, all bound with an audacious hope that the subject under scrutiny is a rational entity which seeks to improve its overall well-being.

Two branches within the subject have evolved thus: microeconomics (individual choices) which deals with entities and the interaction between those entities, while macroeconomics (aggregate outcomes) deals with the entire economy as a whole.

A typical college student appreciates the lessons of economics in day-to-day life. Semester books (choices) are to be purchased with a limited amount of pocket money (constraints).

The aim of studying economics is to understand the decision process behind allocating the currently available resources, the needs always unlimited but resources being limited.

Adam Smith wrote ‘An inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations‘ which as the name suggests, was an attempt at understanding the reasons behind the economic growth (or lack thereof) of a nation.

An interesting backdrop to consider here — the fundamental assumption that we need to make for the whole economic system (as we know it today) to work is that human beings are motivated by pure self-interest and will take decisions that they think will make them ‘better off’ now or sometime in the future.

The economic and political systems of a country are closely inter-linked and jointly determine the well-being of its citizens.

Success Criteria: I can/have...

- Explain and apply concepts to analyse the Economic world

Activities:

- Google classroom

-

Introduction to Economics cont...

What is Economics?

Economics Definition: Economics is essentially a study of the usage of resources under specific constraints, all bound with an audacious hope that the subject under scrutiny is a rational entity which seeks to improve its overall well-being. Simply put, Economics is the study of people and choices.

Two branches within the subject have evolved thus: microeconomics (individual choices) which deals with entities and the interaction between those entities, while macroeconomics (aggregate outcomes) deals with the entire economy as a whole.

A typical college student appreciates the lessons of economics in day-to-day life. Semester books (choices) are to be purchased with a limited amount of pocket money (constraints).

The aim of studying economics is to understand the decision process behind allocating the currently available resources, the needs always unlimited but resources being limited.

Adam Smith wrote ‘An inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations‘ which as the name suggests, was an attempt at understanding the reasons behind the economic growth (or lack thereof) of a nation.

An interesting backdrop to consider here — the fundamental assumption that we need to make for the whole economic system (as we know it today) to work is that human beings are motivated by pure self-interest and will take decisions that they think will make them ‘better off’ now or sometime in the future.

The economic and political systems of a country are closely inter-linked and jointly determine the well-being of its citizens.Success Criteria: I can/have...

- Explain and apply key concepts to analyse the Economic world

- Google classroom

- Education Perfect

-

Kia ora...This week we are exploring the key concepts of the Economic world in order to be able to apply our understanding by setting up our own ideal economy.

Success Criteria: I can/have...

- setup an economic system using key concepts from the Economic world

Activities:

- Economic theory - google classroom

- Stranded on an Island - google classroom

-

Kia ora 9C2, this week we are applying our understandings of both economics and socioeconomics in the construction of your ideal economic system. You have a clear set of values from which to assess your choices and reflect upon the opportunity costs. The next step is to integrate our natural resources into the economy, while maintaining clear explanations of how the choices your team has made are justified.

The overall activity this week remains the structuring of your team's economy, the learning however will be related to the production cycle and social impacts of the industries that have grown around the resources you have discovered on the island.

Success Criteria: I can/have...

- Connect my team's economic policies and plans to the set of values which underpin our ideal economy

- Explain how the natural resources on the island relate to the economic world of production

- Explain how the production cycle of the industries who use these natural resources have and impact on the social world (by looking at the production process & how it intersects with human rights)

Activities:

- Completing production plan for Economy

- Engaging with the creation of the policies your economy will function on

- Natural Resources - Investigating the production cycle (or supply line) and its connection to human rights

Homework:

- Predict the nature of one of the problems your economy may face in next week's problem-set; think about how your economy would adapt, if your prediction was accurate.Natural resources and the paradox of infinite growth

That the limited availability of natural resources may threaten economic growth has preoccupied economists since the birth of the discipline. Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, and other classical economists have paid so much attention to the limits to growth caused by finite natural resources that they have given these limits a central role in their analysis of the long-term dynamic evolution of market economies towards a stationary state. The gloomy conclusions reached by those early economists have received a modern formulation and further support in recent years with the works of G. Hardin and Baden, 1977; and H. S. D. Cole et al., 1973.

Modern economic theory allows us to distinguish between different characteristics of natural resources which are directly relevant to the problem in question. A resource is said to be exhaustible if one can find a pattern of use for this resource such that it will be depleted in finite time. Clearly, almost any natural resource, with perhaps the exception of solar energy, is exhaustible. A resource is said to be renewable if one can find a pattern of positive use such that its stock does not shrink over time. One can think of a fishery or of soil fertility as good illustrations of a renewable resource. Of course, if concern is about the issue of economic development and the possible constraints which natural resources may place on it, interest will naturally focus on the analysis of exhaustible and non-renewable resources which are essential. The definition of the latter concept is intuitive, though, as we shall see, it is not very useful: a resource is essential in production if 'the output of final goods is nil in the absence of the resource' (Dasgupta and Heal, 1974: 4). A similar definition can be used for a resource essential in consumption.

As pointed out by Stiglitz (1974), there are at least three ways to counterbalance the negative effects of essential resources on production: technical progress, increasing returns to scale, and substitution. The third factor needs to be examined in detail. Three different situations may again arise when one analyses the possibilities for substituting a reproducible input, say capital, to an increasingly scarce essential resource.

References:

- Cole, H. S. A., et al., 1973, Thinking about the Future: ,4 Critique of the Limits to Growth (Chatto & Windus, for Sussex University Press).

Hardin, G., 1968, 'The Tragedy of the Commons', Science, 162: 1243-48.

——and J. Baden (eds.) (1977), Managing the Commons (San Francisco: W. H. Freeman & Co.): 8 15.

Stiglitz, J., 1974, 'Growth with Exhaustible Natural Resources: The Competitive Economy', Review of Economic Studies, Symposium on the Economics of Exhaustible Resources, 41: 123-38.

——1976, 'The Efficiency Wage Hypothesis, Surplus Labour and the Distribution of Income in LDCs', Oxford Economic Papers, 28/2: 185-207.

Dasgupta, P., 1988, 'Trust as a Commodity', in D. Gambetta (ed.), Trust-Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations (Oxford: Blackwell): 49-72.

——1993, An Inquiry Into Well-Being and Destitution (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

——and G. Heal, 1974, 'The Optimal Depletion of Exhaustible Resources', Review of Economic Studies, Symposium on the Economics of Exhaustible Resources, 41: 3-28.

——1979, Economic Theory and Exhaustible Resources (Cambridge: Nisbet & Co. Ltd and Cambridge University Press).

-

Kia ora…

It is disappointing to know that racism is still a centrally important issue that society is yet to come to terms with in 2020.

As protests sparked by the death of George Floyd unfold across the US, David Mayeda, senior lecturer in sociology and criminology at the University of Auckland, has a message for NZ: 'For those of you who don’t experience racism, be publicly anti-racist - support those of us who do'.

By now, most of us are aware of the protests unfolding across the United States, sparked by the recent murder of George Floyd at the hands (well, knee) of former Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin.

Floyd was an African American man. Chauvin is white, as are two of the officers who watched passively as Chauvin drove his knee into the back of Floyd’s neck for over eight minutes, ultimately killing him. A fourth officer who stood idly by is Asian American.

As has become increasingly common, bystanders captured on video another example of excessive police force inflicted upon African Americans turned lethal. Those of us who watch these events unfold from afar may watch with horror, anger, frustration, and a range of other understandable emotions. But none of us should watch with surprise.

To understand racism requires us to calculate a range of systemic power inequalities that fester over time, such that we come to accept – disparaging as this may sound – that tragedies like the death of George Floyd reflect an inexcusable social norm.

It is our trying understand the nature of this norm and its many varied forms of expression in society

that will drive our learning focus this term.

that will drive our learning focus this term. This week will be developing our conceptual understandings of concepts like:

Othering

Dominant culture

Three levels of racism

White Supremacy

And others…

In week 3 you will begin your inquiry, this means we have just two weeks of prior learning to develop our understandings of relevant social theories.

Success Criteria: I can/have...

Deepened my understanding of key social concepts and their application to the analysis of race and racism

Activities:

Gallery walk: responding to hip hop culture - is it positive or negative?

March 15th 2019, Sabah & Tyler’s story.

-

This week will be developing our conceptual understandings of concepts like:

Othering

Dominant culture

Three levels of racism

White Supremacy

And others…

In week 3 you will begin your inquiry, this means we have just two weeks of prior learning to develop our understandings of relevant social theories.

Success Criteria: I can/have...

Deepened my understanding of key social concepts and their application to the analysis of race and racism

Activities:

March 15th 2019, Sabah & Tyler’s story.

-

Defining “neutrality”

First, let’s define neutrality.

Here’s the basic idea: if you’re neutral, you don’t take a position. You present all sides fairly and let your reader decide which is correct.

A disputed topic is treated neutrally if each viewpoint about it is not asserted but rather presented (1) as sympathetically as possible, bearing in mind that other, competing views must be represented as well, and (2) with an equitable amount of space being allotted to each, whatever that might be.

On this account, neutrality is a concept dealing specifically with disputed topics, and it has three basic requirements.

First, if an issue that is mentioned in the text is disputed, the text takes no position on the issue. Neutrality is not some midpoint in between competing options. A political moderate’s positions are not “the neutral positions”: they are positions as well. Neutral writing takes no position, left, right, or middle.

Second, there’s the requirement of tone, or the strength of the case made for a viewpoint. Basically, if you’re going to be neutral, you have to represent all the main views about the topic, and you have to represent them all sympathetically, i.e., according to their best, most convincing arguments, evidence, and representatives.

Third, there’s the question of how much space it is fair or equitable to spend in a text on the different sides. Prima facie, it would seem that spending a numerically equal amount of space on both (or all) sides is fair, but it doesn’t always work out that way. Exactly how to apportion limited space is a complex question I’ll address further down.

Basically, to write neutrally is to lay out all sides of any disputed question, without asserting, implying, or insinuating that any one side is correct. If a debated point is mentioned, you represent the state of the debate rather than taking a stand.

As I will explain below, it is probably practically impossible to achieve perfect neutrality, if that were understood to mean neutrality with respect to all cultures and all historical eras. I will also mention the notion of a “good enough” neutrality. One observer noticed that these concessions seem to commit me to the proposition that neutrality comes in gradations or aspects—which is something I happily admit. What I advocate might be described as a strict or professional standard of neutrality.

2. Some principles of neutrality

Here are some general principles that are more or less implied by this definition. I don’t claim that these principles have no exceptions but only that they give a fairly good idea of what neutrality entails.

It is impossible to tell reliably what side of a disputed issue the author of the text is on, if the text is neutral with respect to that issue. The text avoids word quantity, choice, and tone that favors one side over another. Both or all sides agree that their side is fairly represented. Barring that, the text will tend to anger or dissatisfy everyone equally, although for different reasons. Generally, there is a focus on or preference for agreed-upon “facts.” If an opinion is included, it is attributed to a source. The debate is not engaged but rather described and characterized, including information about proportions of people on the different sides, where available. Controversial claims—i.e., claims that a party to a dispute might want to take issue with—are all attributed to specific sources. The author does not personally assert such claims. Biased sources are either eschewed or used in approximately equal numbers on both or all sides throughout a document. A document that uses many biased sources on only one side looks biased itself. When there is a “significant” (this word admittedly glosses over an important problem) ongoing debate and a source implies a definite stand on it in an article that is not about that debate, at the very least there must be some acknowledgment in the text that a disagreement exists. When it makes no sense for articles to be individually neutral, reporting and publications that are neutral with respect to a debate, or a field, will publish in equal amounts on both or all sides of an issue. If a publication favors one side because more papers are received on that side, or because more of the research community embraces that side, that might appear fair and reasonable, but it is not neutral and equally balanced: it will tend to make one side look better than the other.

(2-3 week recurrence through various avenues into the subject-matter)

Learning Objectives:

- To deepen our understanding of the different categories (sometimes called 'levels') of racism.

- To recognise how our prior learning about the concepts of Othering etc. are applied in different ways in analysis, depending on the social context wherein interactions demonstrate real-life impacts which warrant considered analysis.

- Recognise the applicable uses of our already learned sociological concepts in analysis of the political contexts and impacts connected to racism.

- Demonstrate my understanding that social scholarship unavoidably engages with, and critically evaluates, different perspectives and the viewpoints their reasoning supports.

- Develop a nuanced view of social issues that can selectively prioritise the significant information for my view of the issue, using the most important ideas, and analysis, provided by the different perspectives I engage with.

-

Defining “neutrality”

First, let’s define neutrality.

Here’s the basic idea: if you’re neutral, you don’t take a position. You present all sides fairly and let your reader decide which is correct.

A disputed topic is treated neutrally if each viewpoint about it is not asserted but rather presented (1) as sympathetically as possible, bearing in mind that other, competing views must be represented as well, and (2) with an equitable amount of space being allotted to each, whatever that might be.

On this account, neutrality is a concept dealing specifically with disputed topics, and it has three basic requirements.

First, if an issue that is mentioned in the text is disputed, the text takes no position on the issue. Neutrality is not some midpoint in between competing options. A political moderate’s positions are not “the neutral positions”: they are positions as well. Neutral writing takes no position, left, right, or middle.

Second, there’s the requirement of tone, or the strength of the case made for a viewpoint. Basically, if you’re going to be neutral, you have to represent all the main views about the topic, and you have to represent them all sympathetically, i.e., according to their best, most convincing arguments, evidence, and representatives.

Third, there’s the question of how much space it is fair or equitable to spend in a text on the different sides. Prima facie, it would seem that spending a numerically equal amount of space on both (or all) sides is fair, but it doesn’t always work out that way. Exactly how to apportion limited space is a complex question I’ll address further down.

Basically, to write neutrally is to lay out all sides of any disputed question, without asserting, implying, or insinuating that any one side is correct. If a debated point is mentioned, you represent the state of the debate rather than taking a stand.

As I will explain below, it is probably practically impossible to achieve perfect neutrality, if that were understood to mean neutrality with respect to all cultures and all historical eras. I will also mention the notion of a “good enough” neutrality. One observer noticed that these concessions seem to commit me to the proposition that neutrality comes in gradations or aspects—which is something I happily admit. What I advocate might be described as a strict or professional standard of neutrality.

2. Some principles of neutrality

Here are some general principles that are more or less implied by this definition. I don’t claim that these principles have no exceptions but only that they give a fairly good idea of what neutrality entails.

It is impossible to tell reliably what side of a disputed issue the author of the text is on, if the text is neutral with respect to that issue. The text avoids word quantity, choice, and tone that favors one side over another. Both or all sides agree that their side is fairly represented. Barring that, the text will tend to anger or dissatisfy everyone equally, although for different reasons. Generally, there is a focus on or preference for agreed-upon “facts.” If an opinion is included, it is attributed to a source. The debate is not engaged but rather described and characterized, including information about proportions of people on the different sides, where available. Controversial claims—i.e., claims that a party to a dispute might want to take issue with—are all attributed to specific sources. The author does not personally assert such claims. Biased sources are either eschewed or used in approximately equal numbers on both or all sides throughout a document. A document that uses many biased sources on only one side looks biased itself. When there is a “significant” (this word admittedly glosses over an important problem) ongoing debate and a source implies a definite stand on it in an article that is not about that debate, at the very least there must be some acknowledgment in the text that a disagreement exists. When it makes no sense for articles to be individually neutral, reporting and publications that are neutral with respect to a debate, or a field, will publish in equal amounts on both or all sides of an issue. If a publication favors one side because more papers are received on that side, or because more of the research community embraces that side, that might appear fair and reasonable, but it is not neutral and equally balanced: it will tend to make one side look better than the other.

(2-3 week recurrence through various avenues into the subject-matter)

Learning Objectives:

- To deepen our understanding of the different categories (sometimes called 'levels') of racism.

- To recognise how our prior learning about the concepts of Othering etc. are applied in different ways in analysis, depending on the social context wherein interactions demonstrate real-life impacts which warrant considered analysis.

- Recognise the applicable uses of our already learned sociological concepts in analysis of the political contexts and impacts connected to racism.

- Demonstrate my understanding that social scholarship unavoidably engages with, and critically evaluates, different perspectives and the viewpoints their reasoning supports.

- Develop a nuanced view of social issues that can selectively prioritise the significant information for my view of the issue, using the most important ideas, and analysis, provided by the different perspectives I engage with.

-

Learning Objective:

- Make connections between race, racism, and racialised political beliefs; and, the histories of Colonialism.

- To understand the historical continuity (13th century - 21st century time-scale) that Te Tiriti o Waitangi sits within and how this contributes to the NZ experience of race, racism, and racialised political beliefs.

- To recognise the ideological significance of the "Doctrine of Discovery" in connection to contemporary forms of racism.

- Recognise & identify the influence of history of present-day social circumstances.

- Discuss the status of race and racism in NZ's context with reference to critical moments in the history of European Monarchy and its motivations for creating racial categories.

- Begin to conceptualise how some ideas, like 'race' for example, are socially constructed, yet even as a belief only, can still cause consequences that have harmful impacts on the lives of marginalised groups.

Discussion on the special theme for the year: “The Doctrine of Discovery: its enduring impact on indigenous peoples and the right to redress for past conquests (articles 28 and 37 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples)”.

Delivered by Moana Jackson

Mr Chair,

Others on this panel who are far more expert than I have already covered much of the history and the basic unjust illogicality of the Doctrine of Discovery. I would like to focus briefly on one part of the doctrine that is perhaps often overlooked, and then devote most of my time to what may be called an indigenous re-discovery of our own rights, law and sovereign authority.

First of all though, I would like to urge us all to remember that while the Doctrine of Discovery was always promoted in the first instance as an authority to claim the land of indigenous peoples, there were much broader assumptions implicit in the doctrine. For to open up an indigenous land to the gaze of the colonising “other”, there is also in their view an opening up of everything that was in and of the land being claimed. Thus, if the Doctrine of Discovery suggested a right to take control of another nation’s land, it necessarily also implied a right to take over the lives and authority of the people to whom the land belonged. It was in that sense, and remains to this day, a piece of genocidal legal magic that could, with the waving of a flag or the reciting of a proclamation, assert that the land allegedly being discovered henceforth belonged to someone else, and that the people of that land were necessarily subordinate to the colonisers. Rather like the doctrine of terra nullius or indeed the very notion in British colonising law of aboriginal title, the Doctrine of Discovery opened up the bodies and souls of indigenous peoples to a colonising gaze which only saw them as inferior, subordinate, and in fact less human than them.

At its most base, it expresses the fundamental and violent racism which has led to the oppression of millions of indigenous peoples over the last several hundred years. It was 2 | 4 thus more than a mere doctrine with unfortunate consequences: it was in fact, and remains to this day, a crime against humanity. And like any crime, it has had, and continues to have, many different manifestations as states continue to exercise the power to dominate which they believe the doctrine has given to them.

In my view, it will therefore not be sufficient for states or churches or others who have profited from the doctrine to merely reject it in the 21st century as an unfortunate product of another time. Neither will it be sufficient for states or churches to simply apologise for its invention and use (important though that is), but rather to actively seek to undo its consequences in practical and meaningful ways.In effect, any colonising rejection of the doctrine, any apology, will be meaningless unless wit, wisdom, and compassion is applied to a practical and proper recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples as defined by the indigenous peoples themselves. The aim should be not just to recompense for the past actions but to accept that a better and more just future for indigenous peoples will ultimately require a restoration of the political and constitutional authority which the colonising states have so consistently sought to suppress.

For full presentation: http://www.apc.org.nz/pma/mj070512.pdf

-

The Race Theory

of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was based on bad science and ideas that are discredited by people who study genetics today. It is worth exploring them nevertheless, not only to better understand the history of racism but also because these ideas continue to reverberate in the way some people talk about racial differences today. Twenty-first-century view race primarily as a social category that plays a role in how people interact with each other (often negatively). While there are minuscule genetic differences between groups, those have no effect on the moral, intellectual, or dispositional differences between them.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, scientists and anthropologists began to talk about the differences between Europeans and the indigenous population in terms of race. During that time, many scientists had begun to promote the idea that different races had different hereditary makeups and, as a result, had different physical and mental capacities. They decided that some races—usually theirs—were superior to others. Soon scholars, politicians, clergymen, artists, and others began to use pejorative terms such as redskin to mark the differences between the indigenous people and the Europeans.

Among the first supporters of racial science was the American anthropologist Samuel George Morton. Building on the common observation that human beings have bigger brains and more skills than any other animal species, Morton falsely speculated (with very little evidence) that the same is true within the human species; a person’s intelligence, personality, and morality, he assumed, were linked to skull size.

Smarter groups or races have larger brains and are therefore more advanced than others, Morton theorized, and he claimed that this was an “objective” way to rank the different races he identified. Morton also believed that the larger a group’s skull capacity, the more “civilized” the group could be. Scientists have long since discredited these ideas.

Drawing from his pseudo-scientific research, Morton grouped people based on their physical features and compiled characterizations of each “race” into an 1839 volume called Crania Americana. In the excerpts below, Morton contrasts descriptions of Europeans, Native Americans, and Africans.

-

Learning Objective:

- Make connections between race, racism, and racialised political beliefs; and, the histories of Colonialism.

- To understand the historical continuity (13th century - 21st century time-scale) that Te Tiriti o Waitangi sits within and how this contributes to the NZ experience of race, racism, and racialised political beliefs.

- To recognise the ideological significance of the "Doctrine of Discovery" in connection to contemporary forms of racism.

- Recognise & identify the influence of history of present-day social circumstances.

- Discuss the status of race and racism in NZ's context with reference to critical moments in the history of European Monarchy and its motivations for creating racial categories.

- Begin to conceptualise how some ideas, like 'race' for example, are socially constructed, yet even as a belief only, can still cause consequences that have harmful impacts on the lives of marginalised groups.

Discussion on the special theme for the year: “The Doctrine of Discovery: its enduring impact on indigenous peoples and the right to redress for past conquests (articles 28 and 37 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples)”.

Delivered by Moana Jackson

Mr Chair,

Others on this panel who are far more expert than I have already covered much of the history and the basic unjust illogicality of the Doctrine of Discovery. I would like to focus briefly on one part of the doctrine that is perhaps often overlooked, and then devote most of my time to what may be called an indigenous re-discovery of our own rights, law and sovereign authority.

First of all though, I would like to urge us all to remember that while the Doctrine of Discovery was always promoted in the first instance as an authority to claim the land of indigenous peoples, there were much broader assumptions implicit in the doctrine. For to open up an indigenous land to the gaze of the colonising “other”, there is also in their view an opening up of everything that was in and of the land being claimed. Thus, if the Doctrine of Discovery suggested a right to take control of another nation’s land, it necessarily also implied a right to take over the lives and authority of the people to whom the land belonged. It was in that sense, and remains to this day, a piece of genocidal legal magic that could, with the waving of a flag or the reciting of a proclamation, assert that the land allegedly being discovered henceforth belonged to someone else, and that the people of that land were necessarily subordinate to the colonisers. Rather like the doctrine of terra nullius or indeed the very notion in British colonising law of aboriginal title, the Doctrine of Discovery opened up the bodies and souls of indigenous peoples to a colonising gaze which only saw them as inferior, subordinate, and in fact less human than them.

At its most base, it expresses the fundamental and violent racism which has led to the oppression of millions of indigenous peoples over the last several hundred years. It was 2 | 4 thus more than a mere doctrine with unfortunate consequences: it was in fact, and remains to this day, a crime against humanity. And like any crime, it has had, and continues to have, many different manifestations as states continue to exercise the power to dominate which they believe the doctrine has given to them.

In my view, it will therefore not be sufficient for states or churches or others who have profited from the doctrine to merely reject it in the 21st century as an unfortunate product of another time. Neither will it be sufficient for states or churches to simply apologise for its invention and use (important though that is), but rather to actively seek to undo its consequences in practical and meaningful ways.In effect, any colonising rejection of the doctrine, any apology, will be meaningless unless wit, wisdom, and compassion is applied to a practical and proper recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples as defined by the indigenous peoples themselves. The aim should be not just to recompense for the past actions but to accept that a better and more just future for indigenous peoples will ultimately require a restoration of the political and constitutional authority which the colonising states have so consistently sought to suppress.

For full presentation: http://www.apc.org.nz/pma/mj070512.pdf

-

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING...a range of ways at looking at well-being integrating a range of sources to discover the huge variety of well-being practices available to students in Aotearoa

- We are synthesising and organising information through our investigation ways in which we can access and contribute to the well-being of ourselves and the wider community

- We will aim to explore a range of wellbeing activities to do both in MHJC and in the community. Outcome: produce a Wellbeing Guide for the Community/ reviews of range of activities E.g. 10 things to get outside in Flat Bush/ things to do in MHJC during break times etc. (can be video, brochure, site, etc - details to be confirmed)

orienteering

map reading

exploring community facilities

bubble soccer

clean up the areas we visit

athletics prep?

bird count

smorgasbord of activities - must meet dimensions of hauora

Week 1: Massive idea gathering on PADLET for teachers and students - week 1 school

Success Criteria:

- Contributed to the idea gathering- discuss a range of ways to access and participate in things directed at well-being.

-

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING...a range of ways at looking at well-being integrating a range of sources to discover the huge variety of well-being practices available to students in Aotearoa

- We are synthesising and organising information through our investigation into different ways in which we can access and contribute to the well-being of ourselves and the wider community (combined with Global Studies)

-

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING...the histories of Flatbush via researching in a cooperative environment and prioritising which historical events and accounts will best connect us and the MHJC community to the land we live on.

- We are synthesising historical information via participation, collaboration, and dialogue.

- We are critically evaluating where our information comes from alongside what it communicates.

1. Contribute to an in-depth discussion about local history effectively and confidently.

A) Name the research-based project I expect to plan and do in a collaborative format that extends to all my classmates.

or,

B) Participate in Jigsaw learning with increased understanding of how the integration of information can be accomplished most effectively when questions are raised, ideas are explored, and learning is collaborative.

-

EXPLORE / TŪHURA learning intentions:

- We are EXPLORING...the histories of Flatbush via researching in a cooperative environment and prioritising which historical events and accounts will best connect us and the MHJC community to the land we live on.

- We are synthesising historical information via participation, collaboration, and dialogue.

- We are critically evaluating where our information comes from alongside what it communicates.

1. Contribute to an in-depth discussion about local history effectively and confidently.

A) Name the research-based project I expect to plan and do in a collaborative format that extends to all my classmates.

or,

B) Participate in Jigsaw learning with increased understanding of how the integration of information can be accomplished most effectively when questions are raised, ideas are explored, and learning is collaborative.

-

LO -

- develop an understanding of the concept of tūrangawaewae in terms of how it can be used to analyse the connections held between people and places.

- Discover local histories related to the earliest communities in our Hauraki-Manakau-Tāmaki area

SC -

- apply tūrangawaewae in terms of understanding human geography in NZ

- recount significant histories of the local area

Firstly, we will finish off our interrogation of how different New Zealanders view the significance of Tangata Whenua and their stories. Then,

Our Local Place in Flatbush - what is this place? Years 1200 - 1700

in the late 13th century, the Tainui waka sailed into the Hauraki Gulf and became an enduring part of the story of Auckland and Aotearoa New Zealand.

Using the concept of Tūrangawaewae as a way to try and understand the research we will look at in a deeper way, we will explore these early travels across what we now know as Auckland and reflect on how these stories have come to shape the environment around us today.

Once we have completed a good historical investigation of the relevant research on the early years of the Tainui ventures in the area, you will be tasked with taking on the personality of some person who features in these stories; after doing some fine-tuning research on this person and their life, you will write a "postcard for the future" as them; attempting to adopt their perspective on this place - What was tūrangawaewae for them, and what did this mean to the person?

Extra-background for Experts:

-

https://www.rnz.co.nz/audio/player?audio_id=2500645

LO -

- develop an understanding of the concept of tūrangawaewae in terms of how it can be used to analyse the connections held between people and places.

- Discover local histories related to the earliest communities in our Hauraki-Manakau-Tāmaki area

SC -

- apply tūrangawaewae in terms of understanding human geography in NZ

- recount significant histories of the local area

Firstly, we will finish off our interrogation of how different New Zealanders view the significance of Tangata Whenua and their stories. Then,

Our Local Place in Flatbush - what is this place? Years 1200 - 1700

in the late 13th century, the Tainui waka sailed into the Hauraki Gulf and became an enduring part of the story of Auckland and Aotearoa New Zealand.

Using the concept of Tūrangawaewae as a way to try and understand the research we will look at in a deeper way, we will explore these early travels across what we now know as Auckland and reflect on how these stories have come to shape the environment around us today.

Once we have completed a good historical investigation of the relevant research on the early years of the Tainui ventures in the area, you will be tasked with taking on the personality of some person who features in these stories; after doing some fine-tuning research on this person and their life, you will write a "postcard for the future" as them; attempting to adopt their perspective on this place - What was tūrangawaewae for them, and what did this mean to the person?

Extra-background for Experts:

-

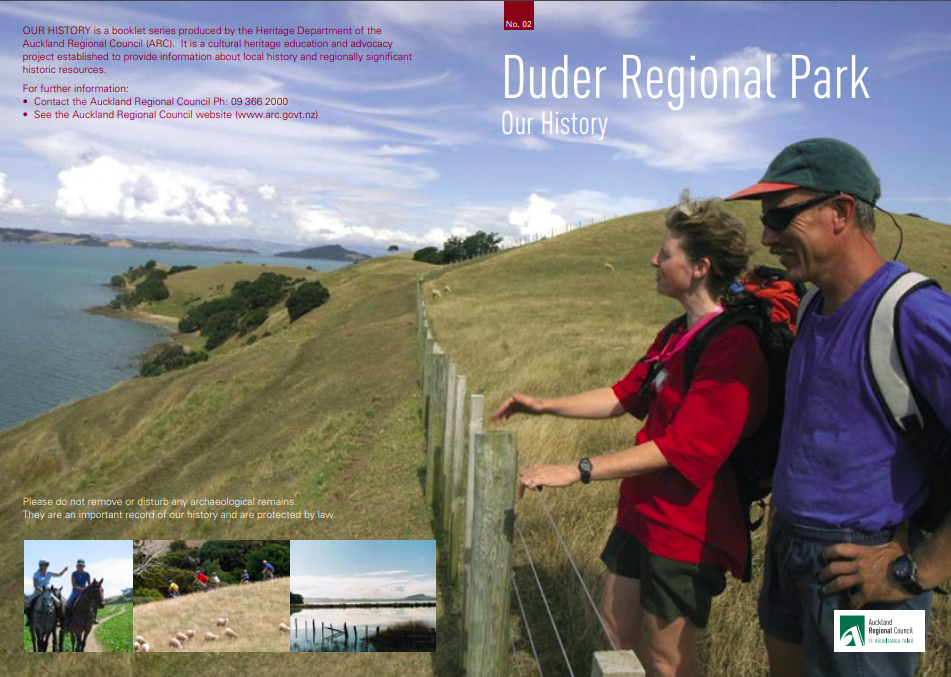

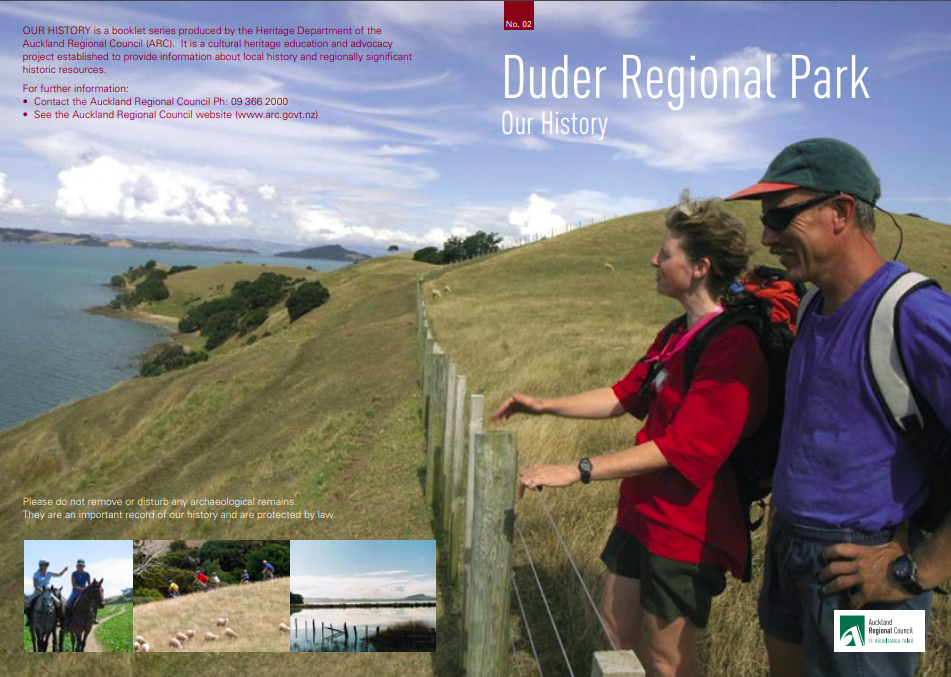

LO's

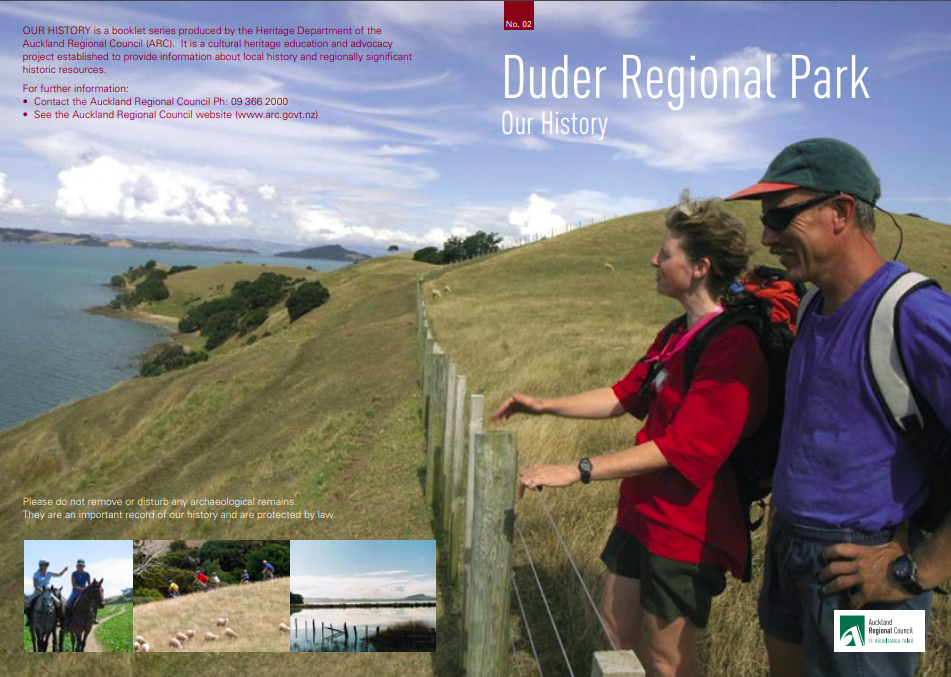

We are planning to create a heritage guide for our local community that resembles this one (linked to below)

OUR HISTORY is a booklet series produced by the Heritage Department of the Auckland Regional Council (ARC).

OUR HISTORY is a booklet series produced by the Heritage Department of the Auckland Regional Council (ARC).It is a cultural heritage education and advocacy project established to provide information about local history and regionally significant historic resources.

For further information: • Contact the Auckland Regional Council Ph: 09 366 2000 • See the Auckland Regional Council website (www.arc.govt.nz) Please do not remove or disturb any archaeological remains. They are an important record of our history and are protected by law.

Duder Regional Park is on the Whakakaiwhara Peninsula at the entrance to the Wairoa River near Clevedon. The Peninsula has a long and rich history, which begins with the visit of the famous Tainui canoe in the 1300s. Ngäi Tai were the first people to live on the Whakakaiwhara Peninsula. They lived there for hundreds of years, building gardens and a pä (defended fortification) on the point. It is an important place to Ngäi Tai because of its Tainui history, the excellent views over the Hauraki Gulf and the availability of food such as shellfish, eels, sharks, and berries and birds from the forest. Thomas Duder purchased the Peninsula and surrounding land from Ngäi Tai in 1866. The Duder family farmed the Peninsula for the next 130 years. For many years, the Peninsula was used as an unfenced grazing area for sheep, while the rest of the farm was developed. From the 1930s, the Duders began converting the Peninsula into a productive farm. This involved 30 years of clearing the scrub, putting up fences, ploughing the land and sowing the pasture. The Peninsula was also a popular place for fishing, picnics, boating and camping. The Auckland Regional Council bought the Whakakaiwhara Peninsula in 1994. Today, visitors can still see signs of the past on the Peninsula, as well as enjoying the pockets of original native forest and some of the best coastal views in the Auckland region.

What to see and do...

• Follow the Farm Loop Walk to Whakakaiwhara Pä and see the earthwork remains of this fortified Mäori settlement (2½ hours return).

• Follow the coastal walk to one of the many beaches. Take your togs, a picnic or your fishing rod, as visitors have done for over 100 years.

• Visit the pockets of original native forest and see the trees and plants Mäori used for eating, weaving, dyeing and building.

• Watch the birdlife and hunt for shells at Duck Bay (Waipokaia). • Join an Auckland Regional Council volunteer day to help out with planting and conservation work. • Follow the orienteering course, go horse-riding (with a permit) or mountain-biking.

-

LO's

We are planning to create a heritage guide for our local community that resembles this one (linked to below)

OUR HISTORY is a booklet series produced by the Heritage Department of the Auckland Regional Council (ARC).

OUR HISTORY is a booklet series produced by the Heritage Department of the Auckland Regional Council (ARC).It is a cultural heritage education and advocacy project established to provide information about local history and regionally significant historic resources.

For further information: • Contact the Auckland Regional Council Ph: 09 366 2000 • See the Auckland Regional Council website (www.arc.govt.nz) Please do not remove or disturb any archaeological remains. They are an important record of our history and are protected by law.

Duder Regional Park is on the Whakakaiwhara Peninsula at the entrance to the Wairoa River near Clevedon. The Peninsula has a long and rich history, which begins with the visit of the famous Tainui canoe in the 1300s. Ngäi Tai were the first people to live on the Whakakaiwhara Peninsula. They lived there for hundreds of years, building gardens and a pä (defended fortification) on the point. It is an important place to Ngäi Tai because of its Tainui history, the excellent views over the Hauraki Gulf and the availability of food such as shellfish, eels, sharks, and berries and birds from the forest. Thomas Duder purchased the Peninsula and surrounding land from Ngäi Tai in 1866. The Duder family farmed the Peninsula for the next 130 years. For many years, the Peninsula was used as an unfenced grazing area for sheep, while the rest of the farm was developed. From the 1930s, the Duders began converting the Peninsula into a productive farm. This involved 30 years of clearing the scrub, putting up fences, ploughing the land and sowing the pasture. The Peninsula was also a popular place for fishing, picnics, boating and camping. The Auckland Regional Council bought the Whakakaiwhara Peninsula in 1994. Today, visitors can still see signs of the past on the Peninsula, as well as enjoying the pockets of original native forest and some of the best coastal views in the Auckland region.

What to see and do...

• Follow the Farm Loop Walk to Whakakaiwhara Pä and see the earthwork remains of this fortified Mäori settlement (2½ hours return).

• Follow the coastal walk to one of the many beaches. Take your togs, a picnic or your fishing rod, as visitors have done for over 100 years.

• Visit the pockets of original native forest and see the trees and plants Mäori used for eating, weaving, dyeing and building.

• Watch the birdlife and hunt for shells at Duck Bay (Waipokaia). • Join an Auckland Regional Council volunteer day to help out with planting and conservation work. • Follow the orienteering course, go horse-riding (with a permit) or mountain-biking.

-

LO's

We are planning to create a heritage guide for our local community that resembles this one (linked to below)

OUR HISTORY is a booklet series produced by the Heritage Department of the Auckland Regional Council (ARC).

OUR HISTORY is a booklet series produced by the Heritage Department of the Auckland Regional Council (ARC).It is a cultural heritage education and advocacy project established to provide information about local history and regionally significant historic resources.

For further information: • Contact the Auckland Regional Council Ph: 09 366 2000 • See the Auckland Regional Council website (www.arc.govt.nz) Please do not remove or disturb any archaeological remains. They are an important record of our history and are protected by law.

Duder Regional Park is on the Whakakaiwhara Peninsula at the entrance to the Wairoa River near Clevedon. The Peninsula has a long and rich history, which begins with the visit of the famous Tainui canoe in the 1300s. Ngäi Tai were the first people to live on the Whakakaiwhara Peninsula. They lived there for hundreds of years, building gardens and a pä (defended fortification) on the point. It is an important place to Ngäi Tai because of its Tainui history, the excellent views over the Hauraki Gulf and the availability of food such as shellfish, eels, sharks, and berries and birds from the forest. Thomas Duder purchased the Peninsula and surrounding land from Ngäi Tai in 1866. The Duder family farmed the Peninsula for the next 130 years. For many years, the Peninsula was used as an unfenced grazing area for sheep, while the rest of the farm was developed. From the 1930s, the Duders began converting the Peninsula into a productive farm. This involved 30 years of clearing the scrub, putting up fences, ploughing the land and sowing the pasture. The Peninsula was also a popular place for fishing, picnics, boating and camping. The Auckland Regional Council bought the Whakakaiwhara Peninsula in 1994. Today, visitors can still see signs of the past on the Peninsula, as well as enjoying the pockets of original native forest and some of the best coastal views in the Auckland region.

What to see and do...

• Follow the Farm Loop Walk to Whakakaiwhara Pä and see the earthwork remains of this fortified Mäori settlement (2½ hours return).

• Follow the coastal walk to one of the many beaches. Take your togs, a picnic or your fishing rod, as visitors have done for over 100 years.

• Visit the pockets of original native forest and see the trees and plants Mäori used for eating, weaving, dyeing and building.

• Watch the birdlife and hunt for shells at Duck Bay (Waipokaia). • Join an Auckland Regional Council volunteer day to help out with planting and conservation work. • Follow the orienteering course, go horse-riding (with a permit) or mountain-biking.